Imperial mansions: the history of the Winter Palace. Apartments of Nicholas II in the Winter Palace Winter Palace during the time of Catherine 2

Small photo selection

On October 10, 1894, Her Highness Princess Alice of Hesse arrived by regular train to Livadia, accompanied by Their Imperial Highnesses Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich and Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna (her older sister). The imminent arrival of the heir to the bride was caused by the critical state of health of Emperor Alexander III, who was supposed to bless the marriage of Cesarevich. The engagement itself took place in Coburg on April 8 of the same year.

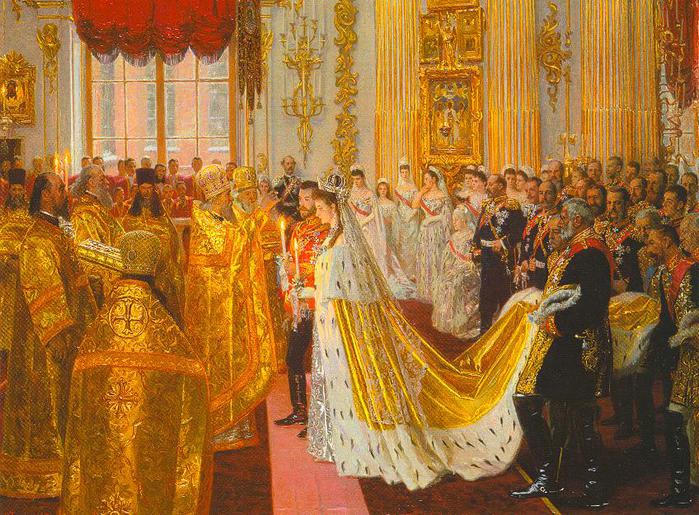

M. Zichy

November 14, 1894 in the Cathedral of the Imperial Winter Palace held the highest wedding.

After the ceremony, the August couple went to the Imperial Anichkov Palace, under the shelter of the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna.

On November 18, Zimny \u200b\u200bvisited the Private Rooms of the newlyweds of Grand Duchess Ksenia Alexandrovna and Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, who were married on July 25. Then the final decision was made to relocate to Winter.

The arrangement of the future Apartment was entrusted to the new Palace Architect A.F. Krasovsky. A place for her was chosen in the second floor of the northwestern part of the palace. The alteration was supposed to be the former chambers of Empress Maria Feodorovna, previously owned by the wife of the Sovereign Nikolai Pavlovich. It should be noted that the magnificent Bryullovsky and Shtakenschneider interiors under Sovereigns Aleksander II and Alexander III did not undergo significant changes. The abundance of gilding, French silk and museum values \u200b\u200bof the canvas did not meet the taste of Tsesarevich and Her Highness. To help academician A.F. Krasovsky, N. I. Kramskoy and S. A. Danini were appointed to reconstruct these chambers. According to the results of the announced competition for the best interior design for the new Imperial chambers, the team included Academician M. E. Mesmakher, architect D. A. Kryzhanovsky and Academician N. V. Nabokov. Joiner's artwork was performed in the best workshops of F. Meltzer, N. Svirsky and Steingolts.

Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna took an active part in the arrangement of the Imperial private chambers. She negotiated with architects and artists. All direct executors of the order had to reckon with her instructions.

In the spring of 1895, the interiors of the new Imperial personal chambers were finally approved in all details. The decoration was carried out as quickly as possible and already on December 16, 1895, after participating in the New Year's charity bazaar in the halls of the Imperial Hermitage, the August couple visited their fully finished chambers in the palace.

Before you begin to get acquainted with the Apartment, you should get some idea of \u200b\u200bthe Imperial Winter Palace. According to a note in 1888, the total area of \u200b\u200bthe palace with the Imperial Hermitage and the building of the Imperial Hermitage Theater occupied 20,719 square meters. soot. or 8 2/3 tithes, the building of the palace itself - 4 902 square meters. Soot., the main courtyard - 1 912 square meters. soot .; The residential floors of the palace contained 1,050 chambers, the floor area of \u200b\u200bwhich was 10,219 square meters. soot. (4 1/4 dess.), And the volume is up to 34 500 cubic meters. soot .; in these chambers there are 6,333 square meters. soot. parquet floors: 548 - marble 2 568 - slab, 324 - pre-finished, 512 - asphalt, mosaic, brick, etc .; doors - 1,786, windows - 1,945, 117 stairs with 3,800 steps, 470 different stoves (after the fire of 1837, the palace was heated according to the method of General Amosov: the stoves were in the basement and the rooms were heated with warm air through the pipes) ; the roof surface of the palace is 5 942 sq. m. soot .; on the roof there are 147 dormers, 33 glass gaps, 329 chimneys with 781 smoke; the length of the cornice surrounding the roof is 927 soot and the stone parapet is 706 soot .; lightning rods - 13. The cost of maintaining the palace extended to 350 thousand rubles. per year with 470 employees.

Plan:

Malachite living room. Anticipated the Personal chambers of Their Majesties. It was part of the Front Neva Enfilade. The ancient ceremonies of the Royal House were held here, courtiers were received, relatives gathered, and numerous Councils of committees headed by Her Majesty met. During court balls, Their Majesties rested in solitude here. From here began the Solemn exits of Their Majesties.

Her Majesty's Salon or Her Majesty's First Living Room. This room, decorated in the Empire style, was intended for the reception of the maid of honor. Restrained decor was done by masters G. Bott, A. Zabelin and painter D. Molinari. Furniture work workshop N.F. Svirsky.

The silver drawing room of Her Majesty, or the Second drawing room of Her Majesty. Living room in the style of Louis XVI. Intended for receptions of Her Majesty's maid of honor and the ladies of the Diplomatic Corps, as well as for Her Majesty's relaxation. Ladies on duty were also here. Her Majesty, who possessed a good soprano, often played music with her associates in this living room. Being a keen collector of French glass, Halle and Daum Her Majesty posted the best examples here.

Her Majesty’s office. It is noteworthy that Her Majesty's particularly respectful attitude to the memory of the former owners of chambers. So, a portrait of the work of Vigee-Lebrun of the first August Hostess, Empress Elizabeth Alekseevna, was installed above Her Majesty’s desktop. A small podium behind the screens in the northwestern corner of the Cabinet served as a viewing platform for admiring the views of North Palmyra.

Her Majesty's bedroom. The modest room of the August couple, with children's furniture belonging to Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna. The decoration is widely used French chintz.

Wardrobe of Her Majesty. Made in the style of Louis XVI.

Boudoir of Her Majesty. Adjacent directly to the Cabinet of His Majesty. Solved in the style of low-key Gothic.

Concluding my acquaintance with Her Majesty's chambers, I would like to say that during the presence of Their Majesties in the palace these rooms were filled with a great many flowers and greenery. Countless vases, pots, flowerpots of various shapes and sizes with roses, orchids, lilies, cyclamens, azaleas, hydrangeas and violets filled the apartments with subtle smells.

Cabinet of His Majesty. Made in the style of Gothic. His Majesty, in memory of his trip to the countries of the Near and Far East, placed many art objects of China, Japan and India. All things were picked up and placed with his own hand. By the way, the Sovereign was versed in Asian culture, sent an expedition to Tibet, assembled a unique collection of Japanese Shung prints (perished in 1918), unique to Russia, even had a small tattoo.

Valet.

The White Dining Room of Their Majesties, or the Small Dining Room of Their Majesties. Made in the style of Louis XVI. The walls were decorated with 18th-century Russian tapestries. It was illuminated by a musical chandelier of English work.

Moorish. Intended for the rest of the courtiers during the Great Imperial balls. In ordinary times, it was used as the ceremonial dining room of Their Majesties.

Library of His Majesty. The only surviving room of Their Majesties' Apartments. Solved in the style of Gothic. As in the Cabinet of His Majesty, the carpentry works were performed by the workshops of N.F. Svirsky. Coats of arms of the Royal House and the House of the Dukes of Hesse were placed on the fireplace. Their Majesties were passionate bibliophiles, subsidized a number of literary and artistic publications (including the famous Diaghilev magazine "World of Art"), had their own book signs. The library served as the official Reception and Front Office of His Majesty. At the same time, she was the most beloved room of the August couple. Here Their Majesties had breakfast, played music, read aloud, sorted out new books, played board games, had a snack in the evenings after the theater or the bathroom, and played with children.

Rotunda. The main hall of the Imperial Palace, in which buffets were set during balls, and during normal times the little Grand Duchesses roller skated there.

Small church.

Billiard Room of His Majesty.

Adjutant of His Majesty. Intended to be on duty at His Majesty.

On the ground floor, exactly under the Personal half of Their Majesties, children's rooms of Their Imperial Highnesses were arranged. The rooms were decorated in modern style.

Visitors who arrived at the palace on official needs entered the Emperor’s apartments through the west, Saltykovsky entrance.

Own Entrance of Their Imperial Majesties.

Nearly nine years of life gave Their Majesty an apartment in the Imperial Winter Palace. Since the summer of 1904, Their Majesties appeared here only during official receptions. The main residence was the Imperial Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo. In 1904, the last high society ball was given in the Empire. In 1915, the Empress arranged an infirmary for the lower ranks in the Grand Enfilade.

To summarize this acquaintance, you should know that all these interiors have not been preserved. Partially surviving exceptions: Rotunda, Moorish, Malachite, Small Canteen, His Majesty's Library.

However, there is a "Inventory of Things Owned by Their Imperial Majesties and Stored in Their Own Rooms in the Winter Palace" compiled by the Chief Overseer of room property in the Imperial Winter Palace and the Imperial Hermitage Nikolai Nikolayevich Dementyev, who held this position from 1888 to 1917. This inventory differs in exact location fixation items and their detailed description.

As an epilogue:

After the fall of the Monarchy, Own half of Their Imperial Majesties was open to the public. In 1918, the palace was plundered by Bolsheviks.

The end of 1918.

Cabinet of the Tsar Liberator.

Wardrobe of Her Majesty.

Her Majesty’s office.

The rooms of the Grand Duchess Tatyana Nikolaevna.

PS - thanks to Vladimir (GUVH) for the idea to make this message.

The development of the territory east of the Admiralty began simultaneously with the emergence of the shipyard. In 1705, a house was erected on the Neva for the "Great Admiralty" - Fedor Matveevich Apraksin. By 1711, the place of the present palace was occupied by the mansions of the nobility involved in the fleet (only naval officials could be built here).

The first wooden Winter House of "Dutch architecture" according to the "exemplary design" of Trezzini under a tiled roof was built in 1711 for the tsar, as for shipbuilding by master Peter Alekseev. In front of its facade in 1718 a canal was dug, which later became the Winter Canal. Peter called him "his office." Specially for the wedding of Peter and Ekaterina Alekseevna, the wooden palace was rebuilt into a modestly decorated two-story stone house with a tiled roof, which had a descent to the Neva. According to some historians, the wedding feast took place in the large hall of this first Winter Palace.

The second Winter Palace was built in 1721 according to the project of Mattarnovi. The main facade, he went to the Neva. In it, Peter lived his last years.

The Third Winter Palace appeared as a result of the reconstruction and expansion of this palace according to the design of Trezzini. Parts of it later became part of the Hermitage Theater created by Quarenghi. During the restoration work, fragments of the Peter's palace inside the theater were discovered: the main courtyard, staircase, canopy, rooms. Now here is essentially the exposition of the Hermitage “Winter Palace of Peter the Great”.

In 1733-1735, according to the project of Bartolomeo Rastrelli, the fourth Winter Palace, the palace of Anna Ivanovna, was built on the site of the former palace of Fedor Apraksin, bought for the empress. Rastrelli used the walls of the luxurious chambers of Apraksin, erected in Peter the Great by the architect Leblon.

The Fourth Winter Palace stood about the same place where we see the current one, and was much more elegant than the previous palaces.

The fifth Winter Palace for the temporary stay of Elizabeth Petrovna and her court was again built by Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli (in Russia it was often called Bartholomew Varfolomeevich). It was a huge wooden building from Moika to Malaya Morskaya and from Nevsky Prospekt to Brick Lane. There is no trace of him for a long time. Many researchers of the history of the creation of the current Winter Palace do not even remember about it, considering the fifth - the modern Winter Palace.

The current Winter Palace is the sixth in a row. It was built from 1754 to 1762 according to the project of Bartolomeo Rastrelli for the Empress Elizabeth Petrovna and is a vivid example of magnificent baroque. But Elizabeth did not have time to live in the palace - she died, so Catherine the second became the first real mistress of the Winter Palace.

In 1837 Zimniy burned down - the fire started in the Field Marshal's Hall and lasted for three days, all this time the ministers of the palace took out works of art that adorned the royal residence, a huge mountain of statues, paintings, precious trinkets grew around the Alexander Column ... They say that nothing was missing ...

The Winter Palace was rebuilt after a fire in 1837 without any major external changes, by 1839 the work was completed, they were led by two architects: Alexander Bryullov (brother of the great Karl) and Vasily Stasov (author of the Savior-Perobrazhensky and Trinity-Izmailovsky cathedrals). The number of sculptures along the perimeter of its roof was only reduced.

For centuries, the color of the facades of the Winter Palace has changed from time to time. Initially, the walls were painted with "sand paint with the finest yellowing", the decor - with white lime. Before the First World War, the palace acquired an unexpected red-brick color, giving the palace a gloomy appearance. A contrasting combination of green walls, white columns, capitals and stucco moldings appeared in 1946.

Exterior of the Winter Palace

Rastrelli built not just the royal residence - the palace was built “for the glory of the All-Russian”, as was said in the decree of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna to the Governing Senate. The palace is distinguished from European Baroque-style buildings by its brightness, cheerfulness of the figurative system, festive solemn elation. Its more than 20-meter height is emphasized by two-tier columns. The vertical division of the palace is continued by statues and vases leading away to the sky. The height of the Winter Palace has become a building standard, elevated to the principle of St. Petersburg city planning. It was not allowed to build above the Winter Building in the old city.

The palace is a giant quadrangle with a large courtyard. The facades of the palace, various in composition, form, as it were, folds of a huge ribbon. The stepped cornice, repeating all the projections of the building, stretched for almost two kilometers. The absence of sharply extended parts along the northern facade, from the Neva (there are only three divisions), reinforces the impression of the length of the building along the embankment; two wings on the west side are facing the Admiralty. The main facade overlooking Palace Square has seven articulations; it is the most ceremonial. In the middle, protruding, part is a triple arcade of the entrance gate, decorated with a magnificent openwork lattice. The southeastern and southwestern risalits are behind the line of the main facade. Historically, it was in them that the living quarters of emperors and empresses were located.

Planning of the Winter Palace

Bartolomeo Rastrelli already had experience in building royal palaces in Tsarskoye Selo and Peterhof. In the scheme of the Winter Palace, he laid the standard planning option, which he had previously tested. The basement of the palace was used as housing for servants or storage rooms. The ground floor housed office and utility rooms. The second floor housed solemn ceremonial halls and personal apartments of the imperial family. The third floor housed maid of honor, doctors and close servants. This layout assumed mainly horizontal connections between the various rooms of the palace, which was reflected in the endless corridors of the Winter Palace.

The northern facade is distinguished by the fact that it houses three huge ceremonial halls. The Neva enfilade included: Small Hall, Big (Nikolaev Hall) and Concert Hall. The large enfilade unfolded along the axis of the Main Staircase, going perpendicular to the Neva Enfilade. It included the Field Marshal Hall, Petrovsky Hall, Armorial (White) Hall Picket (New) Hall. A special place in the series of halls was occupied by the memorial Military Gallery of 1812, the solemn St. George and Apollon Halls. The front rooms included the Pompeii Gallery and the Winter Garden. The route of the royal family through the enfilade of ceremonial halls had a deep meaning. The scenario of the Great Exits worked out to the smallest detail served not only as a demonstration of the full splendor of autocratic power, but also as an appeal to the past and present of Russian history.

As in any other palace of the imperial family, in the Winter there was a church, or rather, two churches: Big and Small. According to Bartolomeo Rastrelli, the Great Church was to serve Empress Elizabeth Petrovna and her “big court”, while the Small Church was to serve the “young court” - the court of Tsarevich’s heir Peter Fedorovich and his wife Ekaterina Alekseevna.

Interiors of the Winter Palace

If the exterior of the palace is made in the style of late Russian Baroque. That interiors are mainly made in the style of early classicism. One of the few interiors of the palace, which retained the original baroque decoration, is the front Jordanian staircase. It occupies a huge space of almost 20-meter height and seems even higher due to the painting of the ceiling. Reflecting in the mirrors, the real space seems even larger. The staircase created by Bartolomeo Rastrelli after the fire of 1837 was restored by Vasily Stasov, preserving the general plan of Rastrelli. The staircase decor is infinitely varied - mirrors, statues, fancy gilded stucco molding, varying the motif of a stylized shell. The forms of Baroque decor became more restrained after replacing wooden columns lined with pink stucco (artificial marble) with monolithic granite columns.

Of the three halls of the Neva Enfilade, the most restrained in finishing the Avantzal. The main decor is concentrated in the upper part of the hall - these are allegorical compositions executed in monochrome technique (grisaille) on a gilded background. Since 1958, a malachite rotunda has been installed in the center of the Avanzal (at first it was in the Tauride Palace, then in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra).

More solemnly decorated the largest hall of the Neva Enfilade - Nikolaevsky. This is one of the largest halls of the Winter Palace, its area is 1103 square meters. The three-quarter columns of the magnificent Corinthian order, the painting of the border of the ceiling and huge chandeliers give it parade. The hall is designed in white.

The concert hall, intended at the end of the 18th century for court concerts, has a more saturated sculptural and picturesque decor than the two previous halls. The hall is decorated with statues of muses, installed in the second tier of walls above the columns. This hall completed the enfilade and was originally conceived by Rastrelli as a threshold to the throne room. In the middle of the 20th century, the silver tomb of Alexander Nevsky (transferred to the Hermitage after the revolution) weighing about 1,500 kg, created at the Mint of St. Petersburg in 1747–1752, was installed in the hall. for the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, in which to this day the relics of the Holy Prince Alexander Nevsky are stored.

The Field Marshal Hall, designed to accommodate portraits of field marshals, begins a large enfilade; he was to give an idea of \u200b\u200bthe political and military history of Russia. Its interior was created, as well as the neighboring Petrovsky (or the Small Throne) Hall, by the architect Auguste Monferand in 1833 and restored after the fire of 1837 by Vasily Stasov. The main purpose of the Peter Hall is memorial - it is dedicated to the memory of Peter the Great, so its decoration is particularly magnificent. In the gilded decor of the frieze, in the painting of the vaults are the coats of arms of the Russian Empire, crowns, wreaths of glory. In a huge niche with a rounded arch is a picture depicting Peter I, led by the goddess Minerva to victories; in the upper part of the side walls are paintings with scenes of the most important battles of the Northern War - at Lesnaya and near Poltava. In the decorative motifs decorating the hall, the monogram of two Latin letters “P”, denoting the name of Peter I, is endlessly repeated - “Petrus Primus”

The coat of arms is decorated with shields with the arms of the Russian provinces of the 19th century, located on huge chandeliers illuminating it. This is an example of late classical style. The porticoes on the end walls conceal the hugeness of the hall, the solid gilding of columns emphasizes its splendor. Four sculptural groups of warriors of Ancient Russia recall the heroic traditions of the defenders of the fatherland and precede the next Gallery of 1812 following it.

The most perfect creation of Stasov in the Winter Palace is the St. George (Great Throne) Hall. The Quarenghi Hall, created in the same place, was killed in the fire of 1837. Stasov, preserving Quarenghi's architectural plan, created a completely different artistic image. The walls are lined with Carrara marble, and columns are carved from it. The decor of the ceiling and columns is made of gilt bronze. The ceiling ornament is repeated in the parquet, recruited from 16 valuable species of wood. Only the Double-headed eagle and St. George are absent in the floor drawing - it is worthless to step on the arms of the great empire. The gilded silver throne was restored to its former place in 2000 by architects and restorers of the Hermitage. Above the throne place is a marble bas-relief with St. George slaying a dragon, the work of Italian sculptor Francesco del Nero.

The owners of the Winter Palace

The customer of the construction was the daughter of Peter the Great, Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, she rushed Rastrelli with the construction of the palace, so the work was carried out at a frantic pace. The Empress’s private chambers (two bedchairs and an office), the rooms of Tsarevich Pavel Petrovich and some adjoining rooms: the Church, the Opera House and the Bright Gallery were hastily finished off. But the empress did not have time to live in the palace. She died in December 1761. The first owner of the Winter Palace was the nephew of the empress (son of her older sister Anna) Peter III Fedorovich. The Winter Palace was solemnly consecrated and commissioned by Easter 1762. Peter III immediately started reworking in the southwestern risalit. The rooms included an office and a library. It was planned to create the Amber Hall on the model of Tsarskoye Selo. For his wife, he determined the chambers in the southwestern risalit, whose windows overlooked the industrial zone of the Admiralty.

The emperor lived in the palace only until June 1762, after which, without even realizing it, he left him forever, moving to his beloved Oranienbaum, where he signed a resignation at the end of July, and soon after that he was killed in the Ropshinsky palace.

The “brilliant century” of Catherine II began, becoming the first real mistress of the Winter Palace, and the southeastern risalit, overlooking Millionnaya Street and Palace Square, became the first of the “zones of residence” of the owners of the palace. After the coup, Catherine II basically continued to live in a wooden Elizabethan palace, and in August she left for Moscow for coronation. Construction work in Zimny \u200b\u200bdid not stop, but other architects were already conducting it: Jean Baptiste Wallen-Delamot, Antonio Rinaldi, Yuri Felten. Rastrelli was first sent on vacation, and then retired. Catherine returned from Moscow in early 1863 and transferred her chambers to the southwestern risalit, showing the continuity from Elizaveta Petrovna to Peter III and to her, the new empress. All work in the west wing turned. At the site of the chambers of Peter III, with the personal participation of the Empress, a complex of personal chambers of Catherine was built. It included: An audio camera, which replaced the Throne Hall; Dining room with two windows; Restroom; two casual bedrooms; Boudoir; Cabinet and Library. All rooms were designed in the style of early classicism. Later, Catherine ordered to remodel one of the daily bedrooms into the Diamond Room or Diamond Quiet, where precious property and imperial regalia were kept: crown, scepter, orb. The regalia were in the center of the room on the table under a crystal cap. As new jewelery was acquired, glazed crates fastened to the walls appeared.

The “brilliant century” of Catherine II began, becoming the first real mistress of the Winter Palace, and the southeastern risalit, overlooking Millionnaya Street and Palace Square, became the first of the “zones of residence” of the owners of the palace. After the coup, Catherine II basically continued to live in a wooden Elizabethan palace, and in August she left for Moscow for coronation. Construction work in Zimny \u200b\u200bdid not stop, but other architects were already conducting it: Jean Baptiste Wallen-Delamot, Antonio Rinaldi, Yuri Felten. Rastrelli was first sent on vacation, and then retired. Catherine returned from Moscow in early 1863 and transferred her chambers to the southwestern risalit, showing the continuity from Elizaveta Petrovna to Peter III and to her, the new empress. All work in the west wing turned. At the site of the chambers of Peter III, with the personal participation of the Empress, a complex of personal chambers of Catherine was built. It included: An audio camera, which replaced the Throne Hall; Dining room with two windows; Restroom; two casual bedrooms; Boudoir; Cabinet and Library. All rooms were designed in the style of early classicism. Later, Catherine ordered to remodel one of the daily bedrooms into the Diamond Room or Diamond Quiet, where precious property and imperial regalia were kept: crown, scepter, orb. The regalia were in the center of the room on the table under a crystal cap. As new jewelery was acquired, glazed crates fastened to the walls appeared.

The empress lived in the Winter Palace for 34 years and her chambers expanded and rebuilt more than once.

Paul I lived in the Winter Palace childhood and youth, and received a gift from his mother Gatchina in the mid 1780s, left him and returned in November 1796, becoming emperor. In the palace, Pavel lived for four years in the redone chambers of Catherine. His large family moved with him, living in their rooms in the western part of the palace. After the accession, he immediately began the construction of the Mikhailovsky Castle, without hiding his plans to literally "strip" the interiors of the Winter Palace, using everything of value to decorate the Mikhailovsky Castle.

After the death of Paul in March 1801, Emperor Alexander I immediately returned to the Winter Palace. The palace returned the status of the main imperial residence. But he did not occupy the chambers of the southeastern risalit, returned to his rooms, located along the western facade of the Winter Palace, with windows to the Admiralty. The premises of the second floor of the southwestern risalit forever lost the significance of the inner chambers of the head of state. They began to repair the chambers of Paul I in 1818, on the eve of the arrival of King Prussia Friedrich Wilhelm III in Russia, appointing “college adviser Karl Rossi” to be responsible for the work. According to his drawings, all design work has been completed. Since that time, rooms in this part of the Winter Palace were officially called the “Prussian-Royal Rooms”, and later - the Second Spare Half of the Winter Palace. It is separated from the First half by the Alexander Hall, in plan this half consisted of two perpendicular suites facing the Palace Square and Millionnaya Street, which were connected in different ways to the rooms facing the courtyard. There was a time when the sons of Alexander II lived in these rooms. First, Nikolai Alexandrovich (who was never destined to become a Russian emperor), and since 1863 his younger brothers Alexander (future emperor Alexander III) and Vladimir. They moved out of the premises of the Winter Palace in the late 1860s, starting their independent life. At the beginning of the twentieth century, dignitaries of the "first level" settled in the rooms of the second spare half, saving them from terrorist bombs. Since the beginning of spring 1905, the Governor-General of St. Petersburg Trepov lived there. Then, in the fall of 1905, Prime Minister Stolypin and his family were settled in these premises.

After the death of Paul in March 1801, Emperor Alexander I immediately returned to the Winter Palace. The palace returned the status of the main imperial residence. But he did not occupy the chambers of the southeastern risalit, returned to his rooms, located along the western facade of the Winter Palace, with windows to the Admiralty. The premises of the second floor of the southwestern risalit forever lost the significance of the inner chambers of the head of state. They began to repair the chambers of Paul I in 1818, on the eve of the arrival of King Prussia Friedrich Wilhelm III in Russia, appointing “college adviser Karl Rossi” to be responsible for the work. According to his drawings, all design work has been completed. Since that time, rooms in this part of the Winter Palace were officially called the “Prussian-Royal Rooms”, and later - the Second Spare Half of the Winter Palace. It is separated from the First half by the Alexander Hall, in plan this half consisted of two perpendicular suites facing the Palace Square and Millionnaya Street, which were connected in different ways to the rooms facing the courtyard. There was a time when the sons of Alexander II lived in these rooms. First, Nikolai Alexandrovich (who was never destined to become a Russian emperor), and since 1863 his younger brothers Alexander (future emperor Alexander III) and Vladimir. They moved out of the premises of the Winter Palace in the late 1860s, starting their independent life. At the beginning of the twentieth century, dignitaries of the "first level" settled in the rooms of the second spare half, saving them from terrorist bombs. Since the beginning of spring 1905, the Governor-General of St. Petersburg Trepov lived there. Then, in the fall of 1905, Prime Minister Stolypin and his family were settled in these premises.

The rooms on the second floor along the southern facade, the windows of which are located to the right and left of the main gate, were still assigned by Paul I to his wife Maria Fedorovna in 1797. Clever, ambitious and strong-willed wife of Paul during her widowhood managed to form a structure called the Office of Empress Maria Fedorovna. It was engaged in charity, education, and providing medical assistance to representatives of various classes. In 1827, repairs were completed in the chambers, which ended in March, and in November of the same year she died. Her third son, Emperor Nicholas I, decided to conserve her chambers. Later, the first reserve half was formed there, consisting of two parallel suites. It was the largest of the palace halves, stretching along the second floor from the White to the Alexander Hall. In 1839, temporary residents settled there: the eldest daughter of Nicholas I, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna and her husband, the Duke of Leuchtenberg. They lived there for almost five years, until the construction of the Mariinsky Palace in 1844 was completed. After the death of Empress Maria Alexandrovna and Emperor Alexander II, their rooms became part of the First Spare Half.

On the ground floor of the southern facade between the empress’s entrance and to the main gate leading to the Bolshoi Dvor, the Palace Grenadiers on duty (2 windows), the Candle post (2 windows) and the Emperor’s Military Campaign Office (3 windows) went to the Palace Square with windows. Next came the premises of the “Hoff-Furrier and Chamber-Furrier Positions”. These rooms ended at the commandant entrance, to the right of which the windows of the commandant’s apartment of the Winter Palace began.

The entire third floor of the southern facade, along the long maid of honor, was occupied by maid of honor apartments. Since these apartments were official office space, by the will of business executives or the emperor himself, maids of honor could be moved from one room to another. Some of the maids of honor quickly getting married, left the Winter Palace forever; others met there not only old age, but also death ...

Under Catherine II, the southwestern risalit was occupied by the palace theater. It was demolished in the mid 1780s to place rooms for the empress’s many grandchildren there. A small enclosed courtyard was arranged inside the risalit. The daughters of the future Emperor Paul I were settled in the rooms of the southwestern risalit. In 1816, Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna married Prince William of Orange and left Russia. Her chambers were redone under the leadership of Carlo Rossi for the Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich and his young wife Alexandra Fedorovna. The couple lived in these rooms for 10 years. After the Grand Duke became Emperor Nicholas I in 1825, the couple moved in 1826 to the northwestern risalit. And after the marriage of the heir-Tsarevich Alesandr Nikolaevich to the Princess of Hesse (future Empress Maria Alexandrovna), they occupied the premises of the second floor of the southwestern risalit. Over time, these rooms became known as the "Half Empress Maria Alexandrovna"

Photos of the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace is the largest palace building in Petersburg. The size and magnificent finish make it possible to attribute it to the most striking monuments of St. Petersburg baroque. “The Winter Palace as a building, as a royal dwelling, may have nothing of the kind in whole Europe. With its immensity, its architecture, it depicts a powerful nation, which has recently entered the midst of educated nations, and with its inner splendor it recalls that inexhaustible life that is boiling in the inside of Russia ... The Winter Palace for us is a representative of all our Russian, Russian, ” - this is how V. A. Zhukovsky wrote about the Winter Palace. The history of this architectural monument is rich in turbulent historical events.

At the beginning of the XVIII century, in the place where the Winter Palace now stands, construction was allowed only to naval officials. Peter I took advantage of this right, being a master of shipbuilding under the name of Peter Alekseev, and in 1708 built a small house in the Dutch style for himself and his family. Ten years later, by order of the future emperor, a canal was dug in front of the side facade of the palace, called (in the palace) the Winter Canal.

In 1711, especially for the wedding of Peter I and Catherine, the architect Georg Mattarnovi, on the orders of the tsar, set about rebuilding the wooden palace into a stone one. In the process, the architect Mattarnovi was removed from business and the construction was led by Domenico Trezzini, an Italian architect of Swiss origin. In 1720, Peter I with his whole family moved from a summer residence to a winter one. In 1723, the Senate was transferred to the Winter Palace. And in January 1725, Peter I died here (in the room on the first floor behind the current second window, counting from the Neva).

Subsequently, the Empress Anna Ioannovna considered the Winter Palace too small and in 1731 entrusted its reconstruction to F. B. Rastrelli, who offered her his project for the reconstruction of the Winter Palace. According to his project, it was necessary to purchase houses that belonged to Count Apraksin, the Maritime Academy, Raguzinsky and Chernyshev, which stood at the time occupied by the current palace. Anna Ioannovna approved the project, the houses were bought up, demolished, and the work began to boil. In 1735, the construction of the palace was completed, and the empress moved to live in it. Here on July 2, 1739 the betrothal of Princess Anna Leopoldovna and Prince Anton-Urikh took place. After the death of Anna Ioannovna, the young emperor John Antonovich was brought here, who stayed here until November 25, 1741, when Elizaveta Petrovna took power into her own hands.

Elizaveta Petrovna also wished to remake the imperial residence to her taste. On January 1, 1752, she decided to expand the Winter Palace, after which neighboring plots of Raguzinsky and Yaguzhinsky were redeemed. In a new place, Rastrelli was building new buildings. According to the draft compiled by him, these buildings had to be attached to the existing ones and be decorated with them in the same style. In December 1752, the empress wished to increase the height of the Winter Palace from 14 to 22 meters. Rastrelli was forced to redo the design of the building, after which he decided to build it in a new place. But Elizaveta Petrovna refused to move the new Winter Palace. As a result, the architect decided to rebuild the entire building. Elizaveta Petrovna signed a new project on the next building of the Winter Palace on June 16, 1754.

The construction lasted eight long years, which fell on the decline of the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna and the short reign of Peter III.

Curious is the story of the arrival in the palace of Peter III. After Elizabeth’s death, 15 thousand dresses, many thousands of shoes and a stocking were left in her wardrobes, and only six silver rubles were in the state treasury. Peter III, who replaced Elizabeth on the throne, wished to immediately enter his new residence. But the Palace Square was cluttered with piles of bricks, boards, logs, barrels of lime and the like construction waste. The capricious temper of the new sovereign was known, and the chief policeman found a way out: in St. Petersburg it was announced that all the townsfolk had the right to take whatever they wanted on Palace Square. A contemporary (A. Bolotov) writes in his memoirs that almost all of Petersburg with wheelbarrows, wagons, and who with sledges (despite the proximity of Easter!) Came running to Palace Square. Clouds of sand and dust rose above her. The inhabitants grabbed everything: planks, bricks, clay, lime, and barrels ... By evening, the square was completely cleaned up. The ceremonial entry of Peter III into the Winter Palace did not interfere.

In the summer of 1762, Peter III was overthrown from the throne. The construction of the Winter Palace was completed already under Catherine II. In the fall of 1763, the empress returned after coronation celebrations from Moscow to Petersburg and became the sovereign mistress of the new palace.

First of all, Catherine suspended Rastrelli from work, and Ivan Betskoi, illegitimate son of Field Marshal Prince Ivan Yuryevich Trubetskoy and personal secretary of Catherine II, became the manager of the construction site. The empress moved the chambers to the southwestern part of the palace, under her rooms she ordered the chambers of her favorite G. G. Orlov to be placed.

From the side of the Palace Square, the Throne Hall was arranged, in front of it appeared a waiting room - the White Hall. Behind the White Hall, a dining room was placed. The Light Cabinet adjoined to it. Behind the dining room was the ceremonial bedchamber, which became a Diamond Quiet a year later. In addition, the empress ordered to arrange for herself a library, an office, a boudoir, two bedrooms and a restroom. Under Catherine, a winter garden and the Romanov Gallery were also built in the Winter Palace. Then the formation of the St. George Hall was completed. In 1764, in Berlin, through agents, Catherine acquired from a businessman I. Gotskovsky a collection of 225 works by Dutch and Flemish artists. Most of the paintings were located in the secluded apartments of the palace, which received the French name "Hermitage" ("place of solitude").

Built by Elizabeth the fourth, the now existing palace is conceived and implemented in the form of a closed quadrangle with an extensive courtyard. Its facades are facing the Neva, towards the Admiralty and the square, in the center of which F. B. Rastrelli intended to put an equestrian statue of Peter I.

The facades of the palace are divided by entablature into two tiers. They are decorated with columns of ionic and composite orders. The columns of the upper tier combine the second, front, and third floors.

The complex rhythm of the columns, the richness and variety of forms of platbands, the abundance of stucco details, the multitude of decorative vases and statues located above the parapet and over the many pediments create the building’s decoration in exceptional splendor and magnificence.

The southern facade is cut by three entrance arches, which emphasizes its importance as the main one. Entrance arches lead to the front courtyard, where the central entrance to the palace was located in the center of the northern building.

The main Jordanian staircase is located in the northeast corner of the building. On the second floor, along the northern facade, there were five large halls of the so-called “anti-chambers”, followed by the huge Throne Hall, and in the southwestern part - the palace theater.

Despite the fact that in 1762 the Winter Palace was completed, for a long time work was still underway on the decoration of the interior. These works were entrusted to the best Russian architects Yu. M. Felten, J. B. Ballen-Delamot and A. Rinaldi.

In the 1780-1790s, work on remaking the interior of the palace was continued by I.E. Starov and J. Quarenghi. In general, the palace was redone and rebuilt an incredible number of times. Each new architect tried to bring something of his own, sometimes destroying what was already built.

Throughout the lower floor there were galleries with arches. Galleries connected all parts of the palace. The rooms on the sides of the galleries were official in nature. There were pantries, a guardroom, and the palace employees lived there.

The ceremonial halls and living quarters of the members of the imperial family were located on the second floor and were built in the Russian Baroque style - huge halls flooded with light, double rows of large windows and mirrors, magnificent decor of Rococo. On the top floor, there were mainly court apartments.

The palace was also destroyed. For example, on December 17-19, 1837 there was a strong fire, which completely destroyed the beautiful finish of the Winter Palace, from which only a charred skeleton remained. Three days could not extinguish the flame, all this time the property taken out of the palace was piled around the Alexander Column. As a result of the disaster, the interiors of Rastrelli, Quarenghi, Montferrand, Rossi died. The restoration work started immediately continued for two years. They were led by architects V.P. Stasov and A.P. Bryullov. According to the order of Nicholas I, the palace was to be restored the same as it was before the fire. However, not everything was so easy to do, for example, only some interiors created or restored after the fire of 1837 by A.P. Bryullov came to us in their original form.

On February 5, 1880, Narodovolets S.N. Khalturin, with the aim of assassinating Alexander II, made an explosion in the Winter Palace. At the same time, eight soldiers from the guard were killed and forty-five wounded, but neither the emperor nor his family members were injured.

At the end of the XIX - beginning of the XX centuries, the internal design was constantly changing and replenished with new elements. Such, in particular, are the interiors of the chambers of Empress Maria Alexandrovna, the wife of Alexander II, created according to the designs of G. A. Bosse (Red Boudoir) and V. A. Shreiber (Golden Living Room), as well as the library of Nicholas II (author A. F. Krasovsky). Among the updated interiors, the most interesting was the decoration of the Nikolaev Hall, in which there was a large equestrian portrait of Emperor Nicholas I by the artist F. Kruger.

For a long time, the Winter Palace was the residence of Russian emperors. After the assassination of Alexander II by terrorists, Emperor Alexander III moved his residence to Gatchina. From that moment on, only particularly solemn ceremonies were held in the Winter Palace. With the accession to the throne of Nicholas II in 1894, the imperial family returned to the palace again.

The most significant changes in the history of the Winter Palace occurred in 1917, along with the Bolsheviks coming to power. A lot of valuables were plundered and damaged by sailors and workers, while the palace was under their control. A direct hit by a shell fired from the guns of the Peter and Paul Fortress damaged the former chambers of Alexander III. Only a few days later the Soviet government declared the Winter Palace and the Hermitage state museums and took the buildings under guard. Soon, valuable palace property and Hermitage collections were sent to Moscow and sheltered in the Kremlin and in the building of the Historical Museum.

A curious story is connected with the October Revolution in the Winter Palace: after the assault on the palace, the Red Guard, who was instructed to place guards for the protection of the Winter Palace, decided to familiarize himself with the placement of guards in pre-revolutionary times. He was surprised to learn that one of the posts has long been on the unremarkable alley of the palace garden (the imperial family called it “Own” and the name was known to Petersburgers under this name). An inquiring Red Guard revealed the history of this post. It turned out that somehow Tsarina Catherine II, going out on the Swinging ground in the morning, saw a sprouted flower there. So that soldiers and passersby would not trample him, Catherine, returning from a walk, ordered a flower guard to be put up. And when the flower withered, the queen forgot to cancel her order for the guard to stay in this place. And since then, for about a year and a half, a guard has been standing at this place, although there was no longer any flower, no tsarina Catherine, or even a Swing platform.

In 1918, part of the premises of the Winter Palace was given over to the Museum of the Revolution, which entailed the reconstruction of their interiors. The Romanov Gallery, in which there were portraits of sovereigns and members of the Romanov dynasty, was completely eliminated. Many chambers of the palace were occupied by a reception center for prisoners of war, a children's colony, a headquarters for arranging mass celebrations, etc. The coat of arms was used for theatrical performances, the Nikolaev Hall was converted into a cinema. In addition, congresses and conferences of various public organizations were repeatedly held in the halls of the palace.

When at the end of 1920 the Hermitage and palace collections returned from Moscow to Petrograd, for many of them there was simply no place. As a result, hundreds of paintings and sculptures went to decorate the mansions and apartments of party, Soviet and military leaders, holiday homes for officials and their families. Since 1922, the premises of the Winter Palace began to be gradually transferred to the Hermitage.

In the early days of World War II, many valuables of the Hermitage were urgently evacuated, some of them were hidden in basements. To prevent fires in the museum’s buildings, the windows were bricked or shuttered. In some rooms, the parquet was covered with a layer of sand.

The Winter Palace was a major target. A large number of bombs and shells exploded near him, and several fell into the building itself. So, on December 29, 1941, a shell crashed into the southern wing of the Winter Palace overlooking the kitchen courtyard, damaging the iron rafters and the roof over an area of \u200b\u200bthree hundred square meters, destroying the fire-fighting water supply installation in the attic. An attic vaulted ceiling of about six square meters was broken. Another shell that hit the podium in front of the Winter Palace damaged the water main.

Despite the difficult conditions that existed in the besieged city, the Mayor’s Executive Committee on May 4, 1942 ordered construction trust No. 16 to carry out priority restoration work in the Hermitage, in which emergency repair workshops took part. In the summer of 1942, they closed the roof in places where it was damaged by shells, partially corrected the formwork, installed broken light lamps or iron sheets, replaced the destroyed metal rafters with temporary wooden rafters, and repaired the water supply system.

On May 12, 1943, a bomb fell into the building of the Winter Palace, partially destroying the roof over the St. George Hall and metal truss structures, and damaged the brickwork of the wall in the pantry of the department of the history of Russian culture. In the summer of 1943, despite shelling, they continued to close up tarred plywood of the roof and ceilings, light lamps. On January 2, 1944, another shell hit the Armorial Hall, severely damaging the finish and destroying two floors. The shell pierced the ceiling of the Nikolaev Hall. But already in August 1944, the Soviet government decided to restore all the museum buildings. Restoration work required tremendous effort and lasted for many years. But, despite all the losses, the Winter Palace remains an outstanding monument of Baroque architecture.

Today, the Winter Palace, together with the buildings of the Small, Big and New Hermitage and the Hermitage Theater, forms a single palace complex, which has little to do in world architecture. In artistic and urban planning, it belongs to the highest achievements of Russian architecture. All the halls of this palace ensemble, built over many years, are occupied by the State Hermitage Museum - the largest museum in the world with huge collections of art.

In the guise of the Winter Palace, which was created, according to the decree on its construction, “for the unified glory of the All-Russian”, in its elegant, festive look, in the magnificent decor of its facades, the artistic and compositional plan of the architect Rastrelli is revealed - a deep architectural connection with the city on the Neva, which has become the capital of the Russian Empire, with all the character of the surrounding city landscape, which continues to this day.

Palace Square

Any tour of the Winter Palace begins on Palace Square. It has its own history, which is no less interesting than the history of the Winter Palace itself. The square was formed in 1754 during the construction of the Winter Palace according to the project of V. Rastrelli. An important role in its formation was played by K. I. Rossi, who in 1819-1829 created the General Staff building and the Ministry building and connected them into a single whole with a magnificent Arc de Triomphe. The Alexander Column took its place in the ensemble of Palace Square in 1830-1834, in honor of the victory in the war of 1812. It is noteworthy that V. Rastrelli intended to place a monument to Peter I in the center of the square. The ensemble of the Headquarters of the Guards Corps, created in 1837-1843 by the architect A.P. Bryullov, completes the ensemble of the Palace Square.

The palace is conceived and built in the form of a closed quadrangle, with an extensive courtyard. The Winter Palace is not small in size and clearly stands out among the surrounding houses.

Countless white columns now gather in groups (especially picturesque and expressive at the corners of the building), then thin out and part, opening windows framed by platbands with lion masks and cupid heads. Dozens of decorative vases and statues are installed on the balustrade. The corners of the building are bordered by columns and pilasters.

Each facade of the Winter Palace is made in its own way. The northern facade facing the Neva stretches more or less even wall, without noticeable protrusions. The south facade, overlooking the Palace Square and having seven articulations, is the main one. Its center is cut by three entrance arches. Behind them is the front yard? where in the middle of the northern building there used to be the main entrance to the palace. Of the side facades, the western one is more interesting, facing the Admiralty and the square on which Rastrelli intended to put the equestrian statue of Peter I cast by his father. Each platband decorating the palace is unique. This is due to the fact that the mass, consisting of a mixture of crushed brick and lime mortar, was cut and processed manually. All stucco decorations of the facades were performed on site.

They painted the Winter Palace in bright colors. The original color of the palace was pink and yellow, as shown by the drawings of the XVIII - the first quarter of the XIX century.

From the interior of the palace, created by Rastrelli, the baroque appearance of the Jordanian staircase and partly the Great Church have been preserved. The main staircase is located in the northeast corner of the building. On it you can see various details of the decor - columns, mirrors, statues, intricate gilded stucco molding, a huge ceiling created by Italian painters. The staircase divided into two solemn marches led to the main, Northern Enfilade, which consisted of five large halls, a fragment of the Jordanian staircase behind which in the north-western risalite was the huge Throne Hall, and in the south-western part - the Palace Theater.

The Big Church, located in the southeast corner of the building, also deserves special attention. Initially, the church was consecrated in honor of the Resurrection of Christ (1762) and secondly - in the name of the Savior of the Image of the Holy Face (1763). Its walls are decorated with stucco molding - an elegant drawing of a floral ornament. The three-tier iconostasis is decorated with icons and picturesque panels depicting biblical scenes. Evangelists on the arches of the ceiling were later written by F.A. Bruni Nowadays, nothing reminds of the former purpose of the church hall, which was ravaged in the 1920s, except for the golden dome and the large picturesque ceiling by F. Fonte Basso, depicting the Resurrection of Christ.

White Hall

It was created by A.P. Bryullov in place of a number of rooms, which had three semicircular windows along the facade in the center, and three rectangular windows on the sides. This circumstance led the architect to the idea of \u200b\u200bdividing the room into three compartments and highlighting the middle one with especially magnificent treatment. The hall is separated from the lateral parts by arches on the protruding pylons, decorated with pilasters, and the central window and the opposite door are underlined by Corinthian columns, over which four statues are placed - female figures representing the arts. The hall is blocked by semicircular arches. The wall against the central windows is designed by arkatura and above each semicircle are placed in pairs bas-relief figures of Juno and Jupiter, Diana and Apollo, Ceres and Mercury and other deities of Olympus.

The arch and all parts of the ceiling above the cornice are finished with caissons and stucco moldings in the same late classical style saturated with decorative elements.

The side compartments are ornamented in the spirit of the Italian Renaissance. Here, under a common crowning cornice, a second smaller order was introduced with Tuscan pilasters covered with small molding with a grotesque ornament. Above the pilasters there is a wide frieze with figures of children engaged in music and dancing, hunting and fishing, reaping and winemaking, or playing navigation and war. Such a combination of architectural elements of various sizes and the overload of the hall with ornaments are characteristic of the classicism of the 1830s, however, the white color gives the hall integrity.

St. George Hall and the Military Gallery

The experts call Georgievsky, or the Great Throne Hall, designed by Quarenghi, the most perfect interior. In order to create the St. George Hall, a special building had to be attached to the center of the eastern facade of the palace. The decoration of this room, which enriched the front suite, found use of colored marble and gilded bronze. At the end of it, on a dais, there used to be a large throne, executed by the master P. Agi. Other well-known architects participated in the design of the palace interiors. In 1826, according to the project of K.I. Rossi, the Military Gallery was built in front of the St. George Hall.

The Military Gallery is a unique monument to the heroic military past of the Russian people. It contains 332 portraits of generals, participants in the Patriotic War of 1812 and the foreign campaign of 1813-1814. Portraits were performed by the famous English artist J. Dow with the participation of Russian painters A.V. Polyakov and V. A. Golike. Most of the portraits were executed from nature, but since in 1819, when the work began, many were no longer alive, some portraits were painted using earlier, preserved images. The gallery occupies a place of honor in the palace and directly adjoins the St. George Hall. The architect K.I. Rossi who built it destroyed the six small rooms that existed here before. The gallery was illuminated through glazed openings in arches supported by arches. The arches rested on groups of twin columns standing against the longitudinal walls. On the plane of the walls in simple gilded frames in five rows were portraits. On one of the end walls, under a canopy, an equestrian portrait of Alexander I by J. Dow was placed. After the fire of 1837, he was replaced by the same portrait of F. Kruger, his painting is in the hall today, on its sides are an image of the King of Prussia Frederick William III, also executed by Kruger, and a portrait of the Austrian emperor Franz I by P. Kraft. If you look at the door leading to St. George's Hall, then on the sides of it you can see portraits of field marshals M.I. Kutuzov and M. B. Barclay de Tolly painted by Dow.

In 1830, A.S. Pushkin often visited the gallery. He immortalized her in the poem "The Leader", dedicated to Barclay de Tolly:

The Russian Tsar in the chamber has a chamber:

She is not rich in gold, not rich in velvet;

But from top to bottom, in full length, around,

His brush free and wide

She was painted by a quick artist.

There are no rural nymphs, no virgin madonnas,

No fauns with bowls, no full-breasted wives,

No dancing, no hunting - but all the raincoats, but swords,

Yes, people full of warlike courage.

In a crowd crowded, the artist placed

Here are the chiefs of our people's forces,

Covered with the glory of a wonderful trip

And the eternal memory of the twelfth year.

The fire of 1837 did not spare the gallery, however, fortunately, all the portraits were taken out by soldiers of the guard regiments.

V.P. Stasov, who restored the gallery, basically retained its former character: he repeated the processing of the walls with double Corinthian columns, left the same arrangement of portraits, and kept the color scheme. But some details of the composition of the hall were changed. Stasov extended the gallery by 12 meters. A balcony was placed over a wide crowning cornice for access to the choirs of adjacent halls, for which they eliminated arches that rested on columns, rhythmically breaking the too long arch into pieces.

After the Great Patriotic War, the gallery was restored, and four portraits of palace grenadiers, veterans who passed the company from 1812-1814 by ordinary soldiers, were additionally placed in it. These works are also performed by J. Dow.

Petrovsky Hall

Petrovsky Hall is also known as the Small Throne Hall. Decorated with particular pomp in the spirit of late classicism, it was created in 1833 by the architect A. A. Montferrand. After the fire, the hall was restored by V.P. Stasov, and its original appearance was preserved almost unchanged. The main difference between the later decoration is associated with the processing of the walls. Previously, the panel on the side walls was divided by one pilaster, now they are placed in two. There was no border around each panel, a large two-headed eagle in the center, and bronze gilded double-headed eagles of the same size were reinforced in diagonal directions on the scarlet velvet upholstery.

The hall is dedicated to the memory of Peter I. Crossed Latin monograms of Peter, double-headed eagles and crowns are included in the motifs of the stucco molding of the capitals of columns and pilasters, friezes on the walls, ceiling paintings and decoration of the entire hall. On two walls there are images of the Poltava battle and the battle of Lesnaya, in the center of the compositions is the figure of Peter I (artists - B. Medici and P. Scotti).

The Winter Palace is without a doubt one of the most famous sights of St. Petersburg

That Winter Palace, which we see today, is actually already the fifth building built on this site. Its construction lasted from 1754 to 1762. Today reminds us of the splendor of the once popular Elizabethan baroque and is, apparently, the crown of creativity of Rastrelli himself

As I already said, there were five Winter Palaces in total on this site, but the whole period of change was invested in a modest 46 years between 1708, when the first was erected and 1754, when the construction of the fifth

The first Winter Palace was a small Dutch-style house erected by Peter the Great for himself and his family.

In 1711, a wooden building was rebuilt into a stone, and this event was timed to the wedding of Peter I and Catherine. In 1720, Peter I and his family moved from a summer residence to a winter residence, in 1723 the Senate was located in the palace, and in 1725 the life of the great emperor was cut short

The new empress, Anna Ioannovna, considered that the Winter Palace was too small for the imperial person, and entrusted him with the reconstruction of Rastrelli. The architect suggested buying the houses standing next to them and demolishing them, which was done, and in place of the old palace and demolished buildings, a new, third in a row, Winter Palace soon grew up, the construction of which was finally completed by 1735. On July 2, 1739, Princess Anna Leopoldovna was solemnly engaged to Prince Anton-Ulrich in this palace, and after the death of the empress, the young emperor John Antonovich, who lived here until November 25, 1741, when Elizaveta Petrovna took power, was transferred here. The new empress was also unhappy with the appearance of the palace, so on January 1, 1752 a couple more houses were bought near the residence, and Rastrelli added a couple of new buildings to the palace. At the end of 1752, the empress considered that it would be nice to increase the height of the palace from 14 to 22 meters. Rastrelli proposed to build the palace in another place, but Elizabeth refused, so the palace was completely dismantled again, and on June 16, 1754 the construction of the new Winter Palace began in its place

The Fourth Winter Palace was temporary: it was built by Rastrelli in 1755 on the corner of Nevsky Prospekt and the Moika embankment during the construction of the fifth. The fourth palace was demolished in 1762, when the construction of the Winter Palace, which we used to see on Petersburg Palace Square today, was completed. The Fifth Winter Palace became the tallest building in the city, but the empress did not survive until the construction was completed - on April 6, 1762 Peter III was admiring the almost finished palace, although he did not live to see the completion of the interior decoration. The emperor was killed in 1762, and the construction of the Winter Palace was finally completed already under Catherine II. The empress suspended Rastrelli from the work, and instead hired Betsky, under whose direction the Throne Hall appeared from the side of Palace Square, in front of which a waiting room was built - the White Hall, behind which the dining room was located. The Light Room adjoined the dining room, and behind it was the ceremonial bedchamber, which later became the Diamond Quiet. In addition, Catherine II took care of creating a library, an imperial study, a boudoir, two bedrooms and a restroom in the palace, in which the empress built a chair from the throne of one of her lovers, the Polish king Ponyatovsky \u003d) By the way, it was under Catherine II that the Winter Palace appeared famous winter garden, Romanov Gallery and St. George Hall

In 1837, the Winter Palace survived a serious test - a major fire, which took more than three days to extinguish. At this time, all the palace property was taken out and piled around the Alexander Column

Another incident in the palace occurred on February 5, 1880, when Khalturin detonated a bomb to kill Alexander II, but as a result only guards were injured - 8 people died and 45 were injured of varying severity

On January 9, 1905, a famous event took place that turned the tide of history: a peaceful working demonstration was shot in front of the Winter Palace, which served as the beginning of the Revolution of 1905-1907. The walls of the palace were never seen by people of imperial blood again - during the First World War there was a military hospital, during the February Revolution, the building was occupied by troops that went over to the side of the rebels, and in July 1917 the Winter Palace was occupied by the Provisional Government. During the October Revolution, on the night of October 25–26, 1917, the Red Guard, revolutionary soldiers and sailors surrounded the Winter Palace, guarded by a garrison of cadets and a women's battalion, and at 2 hours and 10 minutes on the night of October 26, after the famous salvo from the cruiser Aurora , stormed the palace and arrested the Provisional Government - the troops guarding the palace surrendered without a fight

In 1918, part of the Winter Palace, and in 1922 the rest of the building was transferred to the State Hermitage. and Palace Square with the Alexander Column and the General Staff Building form one of the most beautiful and amazing ensembles in the entire post-Soviet space

The Winter Palace is designed in the shape of a square, the facades of which overlook the Neva, Admiralty and Palace Square, and in the center of the main facade there is a front arch

Winter Garden in the Winter Palace)

In the southeast of the second floor is the heritage of the fourth Winter Palace - the Big Church, built under the leadership of Rastrelli

At the disposal of the Winter Palace today more than a thousand different rooms, the design of which amazes and gives the impression of unforgettable solemnity and grandeur

The exterior design of the Winter Palace was, according to the plan of Rastrelli, to architecturally connect it with the ensemble of the Northern capital

The elegance of the palace is emphasized by vases and sculptures, once carved from stone, installed around the entire perimeter of the building above the cornice, which were later replaced at the turn of the XIX-XX centuries with metal analogues

Today in the building of the Winter Palace is the Small Hermitage

Winter Palace. People and walls [History of the imperial residence, 1762–1917] Igor Zimin

The chambers of Catherine II in the last years of her life

In the 1790s Catherine II’s apartments continued to occupy the eastern part of the Winter Palace from the Jordan stairs to half of Pavel Petrovich’s heir (Nos. 283 and 290). The ceremonial half of Empress Catherine II was opened by “two passage chambers” (No. 193), followed by the Arabesque in front of the gallery, to which from the east there was a dining room with chamber-pages and waiters (No. 194). Behind the White Gallery (No. 195) were located: Shtats-Damenskaya (No. 195 - the southeastern part), Before the Shtats-Damenskaya (No. 195 - the eastern part), Buffet Masquerade (No. 196 - the northern part), Large staircase, called the Red ( No. 196 - part), the Pre-Church Hall (No. 270) and the Church in the Name of the Savior of the Miraculous Image (No. 271). From the Pre-Church Hall it was possible to go to the Dining Room (No. 269) and the Buffet Room, where there is the post of the Life Guards Horse Guards Regiment of Reitara (No. 196 - the southern part). In all rooms back in the second half of the 1760s. laid piece, i.e., parquet floors, according to the drawings of Felten and Wallen-Delamot.

The plan of the halls of the southeast risalit

If at the beginning of the reign of Catherine II only half of her nine “chambers” of both representative and purely personal nature were included in her half, then by the end of her reign their number, of course, had changed. This is quite natural, since the empress lived in the Winter Palace for 34 years - all the years of her reign. In the archival documents there is another list of rooms on the half of Empress Catherine II: 1. The main parish and a large entrance staircase; 2. Ceremonial three anti-cameras; 3. Audience (Throne Hall); 4. Dining room; 5. Mundshenk; 6. Stairs to all floors; 7 and 8. Two passage rooms; 9. The front bed; 10. The restroom; 11. Room for valets; 12. The bedchamber; 13. Boudoir; 14. Cabinet; 15. The library; 16. The staircase for Her Majesty; 17. A room with a mezzanine, and in it - a stove-bed; 18. The bedroom; 19 and 20. Two rooms.

Today, only a small part of the chambers of Catherine II preserved the outlines of the 1790s. Numerous redevelopments in subsequent years distorted the appearance and "geography" of the Empress's chambers. For example, the current Aleksandrovsky Hall was occupied by ceremonial rooms: the Council, the Sergeant, “where the Guards are the Unders of the Aficers”, and the Kavalergard (former Kavalerskaya), facing the Palace Square. Behind her was Crony II’s Throne with an audience hall, the Cavalier’s room with a bay window-lantern overlooking the square (No. 280) and the Diamond Room (No. 279) described in detail by us.

You could get into the private chambers of Catherine II from Palace Square by climbing the Small Staircase. This staircase went to the Dining Room (No. 269). Today in its place is the Curfew.

Famous historian M.I. Pylyaev described this part of the Winter Palace as follows: “... having climbed the Small Staircase, we entered a room where, in case of speedy execution of the empress’s orders, a writing desk with an inkwell stood behind the screens for state secretaries. This room was a window to the Small Courtyard; from her entrance was to the restroom; the windows of the last room were on Palace Square. There was a lavatory table, there were two doors from here: one to the right, into the diamond room, and the other to the left, into the bedroom, where the empress usually listened to business in recent years. From the bedroom they directly went into the inner restroom, and to the left - into the study and the mirror room, from which one passage to the lower chambers, and the other directly through the gallery to the so-called “Middle House”; here the empress lived sometimes in the spring ... ".

Behind the Mirror Cabinet mentioned by Pylyaev, the windows on the Small Courtyard housed two rooms of the chamber-jungfer of Catherine II Maria Savvishna Perekusikhina (No. 263–264).

On the mezzanine of the first floor since 1763 there was already mentioned soap, built under the direction of architect J.-B. Wallen-Delamotte and comprising three rooms. According to the descriptions of the 1790s, the bath complex included: Bathhouse (No. 272); under the sacristy of the Big Church (No. 701) there was the Lavatory and directly under the altar there was an extensive Bathhouse with a swimming pool. The bathhouse, or soap-box, was upholstered in “joinery” (linden wood panels) from floor to ceiling. In the upholstered cloth of fawn, the Bathhouse could be descended along a small wooden ladder from the Empress's private chambers. These rooms also overlook Palace Square and Millionnaya Street. Separately, there were “greased boilers for heating water” and a cold water tank. There, on the mezzanine, there was an office with a bedroom for Count Orlov, and later the following favorites lived.

The personal chambers of Catherine II were literally permeated with small ladders. Including secret. Such a secret wooden staircase mezzanines communicated with the Library (from 1764 to 1776). A secret staircase was designed under the mahogany library cabinet so that one of the cabinet doors served as a door through which you could go to the stairs and climb onto the mezzanine. Note that at the beginning of the reign of Catherine II, this was not a game. Secret stairs, and, most likely, not the only one, could be very useful in the era of palace coups.

A very important page in the life of the Winter Palace is connected with the mezzanines of Catherine II. Today, it is generally accepted that the modern State Hermitage Museum, literally “stuffed” with treasures of all times and peoples, “grew up” from the modest mezzanines of Catherine II. These were four small rooms, facing the east of the room, then they were called the Green mezzanines. It was in these rooms that various objects were received, the empress was keen on collecting them at certain times of her life. At first, this collection of rarities was not systematized. However, as the Empress's collections grew, only things of eastern origin remained on the mezzanines, and the mezzanines were called Chinese. Often the empress used mezzanines for dinners in a circle of close people. These rooms exquisitely combined comfort, exoticism and luxury. The Empress liked such a setting.

These historical mezzanines existed until the fire of the Winter Palace in December 1837. Recognizing their historical significance, the mezzanines were then not only not touched, but also periodically repaired. Moreover, they were renovated with the preservation of historical interiors. This is evidenced by a note by the vice-president of the Hoff quartermaster’s office of Count P.I. Kutaisov dated to the beginning of 1833. Then Kutaisov wrote to Nicholas I: “Everything else was influenced by fashion, except for the Chinese mezzanines of the times of the newest, but reminiscent of the reign of Catherine II, so glorious for Russia. Being absolutely sure that the preservation of these monuments is useful both for history and for archeology, I have the honor to present the renewal of these rooms by the present time. This all the more seems to me convenient, since the Chamber of the Meister is very rich in excellent Chinese works that have been lying there for several decades without any use and being uselessly damaged ... ”

Nicholas I approved the proposal P.I. Kutaisova. The restoration of the Chinese mezzanines of Catherine II lasted from 1833 to 1835 under the direction of the architect L.I. Charlemagne 2nd. However, after the fire of 1837, in which the mezzanines died, these rooms did not begin to be restored.

This text is a fact sheet. From the book Imperial Russia the author Anisimov Evgeny ViktorovichThe last years of Catherine II. Favorite of the Zubovs The last years of the reign of Catherine II were marked by a weakening of her creative abilities, a clear stagnation in public life, a rampant favoritism. In general, Catherine in history traces as a libertine, Bacchante, greedy

the author Medvedev Roy AlexandrovichMikoyan in the last years of his life In the last years of his life, Mikoyan paid less and less attention to state affairs. He did not seek meetings with Brezhnev or Kosygin, but he never visited Khrushchev either. In 1967, Mikoyan showed interest in the fate of the Soviet historian.

From the book The Inner Circle of Stalin. Leader's Companions the author Medvedev Roy AlexandrovichThe last years of his life Voroshilov was not deprived of the privileges that he had enjoyed in the past. Therefore, he calmly lived out his last years at a large cottage-estate in the suburbs. His family was small. Voroshilov’s wife, Ekaterina Davydovna, has died. Their children

From the book The Inner Circle of Stalin. Leader's Companions the author Medvedev Roy AlexandrovichThe last years of his life Suslov was not particularly good health. In his youth, he suffered tuberculosis; at a more advanced age, he developed diabetes mellitus. When he worked in Stavropol and Lithuania, after vigorous explanations with one or another employee, he began

From California Daily Life during the Gold Rush author Crete LillianJ. Sutter in the last years of his life. J. Sutter in the last years of his life. 1870s

From the book Russian Fleet in the Mediterranean the author Tarle Evgeny ViktorovichThe last years of his life Already in the very last years of his life, having again entered the service and received the order to become the head of the squadron leaving for the Archipelago, Senyavin in one remarkable order given to his subordinate, Count Heiden, expressed a noble, humane, characteristic

From the book Stalin's Order the author Mironin Sigismund SigismundovichChapter 6 MYTH ABOUT STARIN'S “PARANOJA” IN THE LAST YEARS OF HIS LIFE Almost everyone notes that Stalin’s closest associates were small people for their posts — small as individuals. Here are just the conclusions from this do, as always, the Freudian - that eaten

the author Istomin Sergey Vitalievich From the book of the Marquis de Sade. Great Libertine the author Nechaev Sergey YuryevichLAST YEARS OF LIFE On July 7, 1810, a terrible event occurred in the life of the Marquis de Sade: his wife, the Marquise de Sade, died, who, as we recall, became a nun and devoted her life to charity. Rene Pelage tried her best to atone for the sins of her husband, but he had them

From the book From the Life of Empress Cixi. 1835–1908 the author Semanov Vladimir IvanovichLAST YEARS OF LIFE By the time of the defeat of the Ietheans, the real power of Cixi went downhill, but those around her did not really notice, because the Dowager Empress continued to hold on tightly to the helm of the board and kept a very impressive appearance. Here is how Yu describes her