Bering Sea: geographical location, description. Bering Sea: geographical location, description of the Bering Sea, the ocean to which it belongs

The Bering Strait connects with the Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean Area 2304 thousand km², average depth 1598 m (maximum 4191 m), average water volume 3683 thousand km³, length from north to south 1632 km, from west to east 2408 km.

The shores are predominantly high rocky, heavily indented, forming numerous bays and bays. Most large bays: Anadyrsky and Olyutorsky on the shore, Bristol and Norton in the east. A large number of rivers flow into the Bering Sea, the largest of which are the Anadyr, Apuka in the west, and the Yukon and Kuskokwim in the east. Islands Bering Sea of mainland origin. The largest of them are Karaginsky, St. Lawrence, Nunivak, Pribilof, St. Matthew.

The Bering Sea is the largest of the geosynclinal seas Far East. The bottom topography includes a continental shelf (45% of the area), a continental slope, underwater ridges and a deep-sea trench (36.5% of the area). The shelf occupies the northern and northeastern parts of the sea, characterized by flat terrain, complicated by numerous shoals, basins, flooded valleys and the upper reaches of underwater canyons. Sediments on the shelf are predominantly terrigenous (sands, sandy silts, and coarse clastic near the coast).

The continental slope for the most part has a significant steepness (8-15°), is dissected by underwater canyons, and is often complicated by steps; south of the Pribilof Islands it is flatter and wider. The continental slope of Bristol Bay is complexly dissected by ledges, hills, and depressions, which is associated with intense tectonic fragmentation. The sediments of the continental slope are predominantly terrigenous (sandy silts), with numerous outcrops of bedrock Paleogene and Neogene-Quaternary rocks; in the Bristol Bay area there is a large admixture of volcanic material.

The Shirshov and Bowers submarine ridges are arched rises with volcanic forms. On the Bowers Ridge, diorite outcrops were discovered, which, along with the arc-shaped outlines, brings it closer to the Aleutian island arc. The Shirshov Ridge has a similar structure to the Olyutorsky Ridge, composed of volcanogenic and flysch rocks of the Cretaceous period.

The Shirshov and Bowers submarine ridges separate the deep-sea trench of the Bering Sea. In the west of the basin: Aleutian, or Central (maximum depth 3782 m), Bowers (4097 m) and Komandorskaya (3597 m). The bottom of the basins is a flat abyssal plain, composed of diatomaceous silts on the surface, with a noticeable admixture of volcanogenic material near the Aleutian arc. According to geophysical data, the thickness of the sedimentary layer in deep-sea basins reaches 2.5 km; beneath it lies a basalt layer about 6 km thick. The deep-water part of the Bering Sea is characterized by a suboceanic type of the earth's crust.

The climate is formed under the influence of the adjacent land, the proximity of the polar basin in the north and the open Pacific Ocean in the south and, accordingly, the centers of atmospheric action developing above them. The climate of the northern part of the sea is arctic and subarctic, with pronounced continental features; southern part - temperate, marine. In winter, under the influence of the Aleutian minimum air pressure (998 mbar), a cyclonic circulation develops over the Bering Sea, due to which the eastern part of the sea, where air is brought from the Pacific Ocean, turns out to be somewhat warmer than the western part, which is under the influence of cold Arctic air (which comes with the winter monsoon) . Storms are frequent during this season, the frequency of which in some places reaches 47% per month. Average temperature air in February varies from -23°C in the north to O. -4°C in the south. In summer, the Aleutian Low disappears and winds dominate the Bering Sea. southern directions, which in the western part of the sea are the summer monsoon. Storms are rare in summer. The average air temperature in August varies from 5°C in the north to 10°C in the south. The average annual cloudiness is 5-7 points in the north, 7-8 points per year in the south. Precipitation varies from 200-400 mm per year in the north to 1500 mm per year in the south.

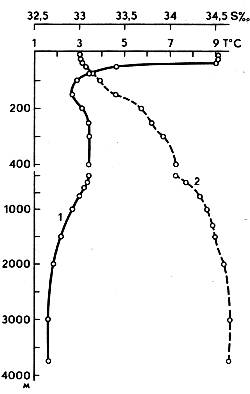

The hydrological regime is determined by climatic conditions, water exchange with the Chukchi Sea and Pacific Ocean, continental runoff and desalination surface waters seas when the ice melts. Surface currents form a counterclockwise gyre, along the eastern periphery of which they flow north warm waters from the Pacific Ocean - the Bering Sea branch of the Kuroshio warm current system. Some of this water flows through the Bering Strait into the Chukchi Sea, the other part deviates to the west and then follows south along the Asian coast, receiving the cold waters of the Chukchi Sea. The South Stream forms the Kamchatka Current, which carries the waters of the Bering Sea into the Pacific Ocean. This current pattern is subject to noticeable changes depending on the prevailing winds. Bering Sea tides are mainly caused by the propagation of tidal waves from the Pacific Ocean. In the western part of the sea (up to 62° north latitude) the highest tide height is 2.4 m, in Cross Bay 3 m, in the eastern part 6.4 m (Bristol Bay). The surface water temperature in February reaches 2°C only in the south and southwest; in the rest of the sea it is below -1°C. In August, temperatures rise to 5°-6°C in the north and 9°-10°C in the south. Salinity influenced river waters and ice melting is significantly lower than in the ocean, and is equal to 32.0-32.5‰, and in the south it reaches 33‰. In coastal areas it decreases to 28-30‰. In the subsurface layer in the northern part of the Bering Sea, the temperature is -1.7 ° C, salinity is up to 33‰. In the southern part of the sea, at a depth of 150 m, the temperature is 1.7°C, salinity is 33.3‰ and more, and in the layer from 400 to 800 m, respectively, more than 3.4°C and more than 34.2‰. At the bottom the temperature is 1.6°C, salinity 34.6‰.

For most of the year, the Bering Sea is covered with floating ice, which in the north begins to form in September - October. In February - March, almost the entire surface is covered with ice, which is carried out into the Pacific Ocean along the Kamchatka Peninsula. The Bering Sea is characterized by the phenomenon of "sea glow".

In accordance with the difference in hydrological conditions of the northern and southern parts of the Bering Sea, the northern part is characterized by representatives of arctic forms of flora and fauna, while the southern part is characterized by boreal ones. The south is home to 240 species of fish, of which there are especially many flounders (flounder, halibut) and salmon (pink salmon, chum salmon, chinook salmon). There are numerous mussels, balanuses, polychaete worms, bryozoans, octopuses, crabs, shrimps, etc. The north is home to 60 species of fish, mainly cod. Among the mammals that characterize the Bering Sea, the fur seal, sea otter, seals, bearded seal, spotted seal, sea lion, gray whale, humpback whale, sperm whale, etc. are typical. The fauna of birds (guillemots, guillemots, puffins, kittiwake gulls, etc.) is abundant. bazaars." In the Bering Sea, intensive whaling is carried out, mainly for sperm whales, as well as fishing and sea animal hunting (fur seal, sea otter, seal, etc.). The Bering Sea is of great transport importance for Russia as a link in the Northern Sea Route. Main ports: Provideniya (Russia), Nome (USA).

The Bering Sea is the largest of the Far Eastern seas washing the shores of Russia, located between two continents - Asia and North America - and is separated from the Pacific Ocean by the islands of the Commander-Aleutian Arc.

The Bering Sea is one of the largest and deepest seas in the world. Its area is 2315 thousand km2, volume - 3796 thousand km3, average depth - 1640 m, greatest depth - 5500 m. The area with depths less than 500 m occupies about half of the entire area of the Bering Sea, which belongs to the marginal seas of the mixed continental-oceanic type.

There are few islands in the vast expanses of the Bering Sea. Not counting the border Aleutian island arc and, in the sea there are: the large Karaginsky Island in the west and several islands (St. Matthew, Nunivak, Pribilof) in the east.

The coastline of the Bering Sea is highly indented. It forms many bays, bays, capes and straits. For the formation of many natural processes of this sea, straits are especially important, providing water exchange with. The waters of the Chukchi Sea have virtually no effect on the Bering Sea, but the Bering Sea waters play a very significant role in.

The continental flow into the sea is approximately 400 km3 per year. Most of the river water ends up in its northernmost part, where the most large rivers: Yukon (176 km3), Kuskokwim (50 km3 per year). About 85% of the total annual flow comes from summer months. The influence of river waters on sea waters is felt mainly in the coastal zone on the northern edge of the sea in summer time.

In the Bering Sea, the main morphological zones are clearly distinguished: the shelf and island shoals, the continental slope, etc. The shelf zone with depths of up to 200 m is mainly located in the northern and eastern parts of the sea and occupies more than 40% of its area. The bottom in this area is a vast, very flat underwater plain 600–1000 km wide, within which there are several islands, troughs and small rises in the bottom. The continental shelf off the coast of Kamchatka and the islands of the Komandorsko-Aleutian ridge is narrow, and its relief is very complex. It borders the shores of geologically young and very mobile land areas, within which there are usually intense and frequent manifestations of seismic activity.

The continental slope extends from northwest to southeast approximately along a line from Cape Navarin to Unimak Island. Together with the island slope zone, it occupies approximately 13% of the sea area and is characterized by a complex bottom. The continental slope zone is dissected by underwater valleys, many of which are typical underwater canyons, deeply cut into the seabed and having steep and even steep slopes.

The deep-water zone (3000–4000 m) is located in the southwestern and central parts sea and is bordered by a relatively narrow strip of coastal shallows. Its area exceeds 40% of the sea area. It is characterized by an almost complete absence of isolated depressions. Among the positive forms, the Shirshov and Bowers ridges stand out. The bottom topography determines the possibility of water exchange between individual parts of the sea.

Different areas of the Bering Sea coast belong to different geomorphological types of shores. Mostly the banks are abrasive, but there are also. The sea is surrounded mainly by high and steep shores, only in the middle part of the western and east coast it is approached by wide strips of flat, low-lying tundra. Narrower strips of low-lying coastline are located near the mouths in the form of a deltaic alluvial valley or border the tops of bays and bays.

Geographical location and large spaces determine the main features of the climate of the Bering Sea. It is almost entirely located in the subarctic climate zone, only the northernmost part belongs to the arctic zone, and the southernmost part belongs to the zone. North of 55–56° N. w. In the seas, continental features are noticeably expressed, but in areas far from the coast they are much less pronounced. To the south of these parallels the climate is mild, typically maritime. Throughout the year, the Bering Sea is under the influence of permanent centers of action - the Polar and Hawaiian maxima. It is no less influenced by seasonal large-scale pressure formations: the Aleutian minimum, the Siberian maximum, and the Asian depression.

In the cold season, northwest, north and northeast winds predominate. Wind speeds in the coastal zone average 6–8 m/s, and in open areas it varies from 6 to 12 m/s. Above the sea, predominantly the masses of continental Arctic and marine polar air interact, at the border of which they form, along which cyclones move to the northeast. The western part of the sea is characterized by storms with wind speeds of up to 30–40 m/s and lasting more than a day.

Average monthly temperature of the coldest months - January and February - is –1…–4°С in the southwestern and southern parts of the sea and – –15…–20°С in the northern and northeastern regions. In the open sea it is higher than in the coastal zone.

In the warm season, southwestern, southern and southeastern winds predominate, the speed of which in the western part open sea 4–6 m/s, and in the eastern regions - 4–7 m/s. In summer, the frequency of storms and wind speeds are lower than in winter. Tropical cyclones () penetrate into the southern part of the sea, causing severe storms with hurricane force. Average monthly air temperatures in the warmest months - July and August - within the sea vary from 4°C in the north to 13°C in the south, and they are higher near the coast than in the open sea.

Water exchange is critical to the water balance of the Bering Sea. Through the Aleutian Straits they receive very large quantities surface and deep ocean waters, and through the waters flow into the Chukchi Sea. Water exchange between sea and ocean affects the temperature distribution, formation of the structure and waters of the Bering Sea.

The bulk of the Bering Sea waters are characterized by a subarctic structure, main feature which is the existence of a cold intermediate layer in summer, as well as a warm intermediate layer located underneath it.

The water temperature on the sea surface generally decreases from south to north, with water in the western part of the sea being somewhat colder than in the eastern part. In coastal shallow areas, surface water temperatures are slightly higher than in open areas of the Bering Sea.

In winter, the surface temperature, equal to approximately 2°C, extends to horizons of 140–150 m, below it rises to approximately 3.5°C at 200–250 m, then its value remains almost unchanged with depth. In summer, the surface water temperature reaches 7–8°C, but drops very sharply (up to 2.5°C) with depth to a horizon of 50 m.

The salinity of the surface waters of the sea varies from 33–33.5‰ in the south to 31‰ in the east and northeast and up to 28.6‰ in the Bering Strait. Water is desalinated most significantly in spring and summer in the areas where the Anadyr, Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers confluence. However, the direction of the main currents along the coasts limits the influence on the deep sea areas. The vertical distribution of salinity is almost the same in all seasons of the year. From the surface to a horizon of 100–125 m, it is approximately equal to 33.2–33.3‰. Salinity increases slightly from horizons of 125–150 m to 200–250 m; deeper it remains almost unchanged to the bottom. In accordance with small spatiotemporal changes in temperature and salinity, the density of water also changes slightly.

The distribution of oceanological characteristics by depth indicates a relatively weak vertical stratification of the waters of the Bering Sea. In combination with strong winds, this creates favorable conditions for the development of wind mixing. In the cold season, it covers the upper layers to horizons of 100–125 m; in the warm season, when the waters are stratified more sharply and the winds are weaker than in autumn and winter, wind mixing penetrates to horizons of 75–100 m in deep areas and up to 50–60 m in coastal areas.

The speeds of constant currents in the sea are low. The highest values (up to 25–50 cm/s) are observed in the areas of the straits, and in the open sea they are equal to 6 cm/s, and the speeds are especially low in the zone of the central cyclonic circulation.

Tides in the Bering Sea are mainly caused by the propagation of tidal waves from the Pacific Ocean. Tidal currents in the open sea are circular in nature, and their speed is 15–60 cm/s. Near the coast and in the straits, the currents are reversible, and their speed reaches 1–2 m/s.

For most of the year, much of the Bering Sea is covered in ice. Ice in the sea is of local origin, that is, it is formed, destroyed and melted in the sea itself. The process of ice formation begins first in the northwestern part of the Bering Sea, where ice appears in October and gradually moves south. Ice appears in the Bering Strait in September. In winter, the strait is filled with solid broken ice, drifting north. However, even during the peak of ice formation, the open part of the Bering Sea is never covered with ice. In the open sea, under the influence of winds and currents, ice is in constant motion, and strong compression often occurs. This leads to the formation of hummocks, the maximum height of which can reach up to 20 m. Fixed ice, which forms in closed bays and bays in winter, can be broken up and carried out to sea during stormy winds. The ice from the eastern part of the sea is carried north into the Chukchi Sea. During July and August the sea is completely clear of ice, but even during these months ice can be found in the Bering Strait. Strong winds contribute to the destruction of the ice cover and the clearing of ice from the sea in summer.

The nature of the distribution of nutrients in the sea is associated with the biological system (product consumption, destruction) and therefore has a pronounced seasonal pattern.

The horizontal and vertical distribution of all forms of nutrients is significantly affected by numerous mesocycles of water, which are associated with patchiness in the distribution of nutrients.

For the Bering Sea, with its highly developed shelf, large and very intense water dynamics, the average annual primary production is estimated at 340 gC/m2.

The annual production of the main groups of aquatic organisms that are components of the Bering Sea ecosystem is (in million tons of wet weight): phytoplankton - 21,735; bacteria - 7607; protozoa - 3105; peaceful zooplankton - 3090; predatory zooplankton - 720; peaceful zoobenthos - 259; predatory zoobenthos - 17.2; fish - 25; squid - 12; bottom commercial invertebrates - 1.42; seabirds and marine mammals - 0.4.

No deposits have yet been discovered on the Russian shelf of the Bering Sea. Within the Eastern coast of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, in the area of the village. Three small oil fields were discovered in Khatyrka: Verkhne-Echinskoye, Verkhne-Telekaiskoye and Uglovoye; A small Zapadno-Ozernoye gas field was discovered in the Anadyr River basin. However, the Bering Sea shelf is assessed as promising for the search for hydrocarbon deposits in Cretaceous, Paleogene and Neogene deposits, and within the Gulf of Anadyr - as a promising placer-bearing region of the Far East.

The coastal parts of the sea are subject to the most intense anthropogenic load: the Anadyr Estuary, Ugolnaya Bay, as well as the shelf of the peninsula (Kamchatka Bay).

The Anadyr Estuary and Ugolnaya Bay are polluted mostly with wastewater from housing and communal services enterprises. Petroleum hydrocarbons and organochlorines enter the Kamchatka Gulf with the flow of the Kamchatka River.

Coastal and open sea areas experience minor heavy metal pollution.

The BERING SEA, a marginal sea in the northern part of the Pacific Ocean between the continents of Eurasia and North America, washes the shores of the USA and Russia (the largest of its Far Eastern seas). It is connected in the north by the Bering Strait to the Chukchi Sea, separated from the Pacific Ocean by the Aleutian chain and the Commander Islands. Area 2315 thousand km 2, volume 3796 thousand km 3. The greatest depth is 5500 m. The coastline is heavily indented, forming many bays (the largest are Karaginsky, Olyutorsky, Anadyrsky - Russia; Norton, Bristol - USA), bays, peninsulas and capes. Karaginsky Islands (Russia), St. Lawrence, Nunivak, Nelson, St. Matthew, Pribilof Islands (USA).

The shores of the Bering Sea are diverse, with predominantly high, rocky, heavily indented bay shores, as well as fjord and abrasion-accumulative shores. Leveled accumulative banks predominate in the east, where the deltas of the large Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers are located.

Relief and geological structure bottom . According to the nature of the bottom topography, the Bering Sea is clearly divided into shallow and deep-water parts approximately along the line from Cape Navarin to Unimak Island. The northern and southeastern parts lie on a shelf with depths of up to 200 m (prevailing depths are 50-80 m) and a width in the northeast of up to 750 km (46% of the sea area) - one of the widest in the World Ocean. It is a vast plain, slightly inclined to the southwest. In the Quaternary period, the shelf periodically drained and a land bridge emerged between the continents of Eurasia and North America. Within the shelf there are large depressions - Anadyr, Navarin, Khatyr and others, filled with Cenozoic terrigenous deposits. Depressions can be reservoirs of oil and natural combustible gas. A narrow continental slope with depths of 200-3000 m (13%) and with large bottom slopes almost throughout its entire length turns into a deep-sea bed with steep ledges, in many places cut by underwater valleys and canyons. The sides of the canyons are often steep and sometimes steep. In the central and southwestern parts there is a deep-water zone with depths of over 3000 m (37%), bordered in the coastal zone by a narrow strip of shelf. The underwater Shirshov Ridge with depths above the ridge of 500-600 m, stretching south from the Olyutorsky Peninsula, divides the deep-water part of the sea into the Komandorskaya and Aleutian basins; it is separated from the island arc by the Ratmanov Trench (depth about 3500 m). The flat bottom of both basins is slightly inclined to the southwest. The Shirshov Ridge is a complex zone of junction of two lithospheric plates (Commander and Aleutian), along which until the mid-Miocene the oceanic crust piled up (possibly with underthrusting). The foundation of the Aleutian Basin is of Early Cretaceous age and is a fragment of the Mesozoic oceanic lithospheric plate Kula, which separated in the Cretaceous from the Pacific plate by a large transform fault, transformed in the Paleogene into the Aleutian island arc and the deep-sea trench of the same name. The thickness of the Cretaceous-Quaternary sedimentary cover in the central part of the Aleutian Basin reaches 3.5-5 km, increasing towards the periphery to 7-9 km. The foundation of the Commander Basin is Cenozoic in age and was formed as a result of local spreading (the spreading of the bottom with the new formation of oceanic crust), which continued until the end of the Miocene. The paleospreading zone can be traced to the east of Karaginsky Island in the form of a narrow trough. The thickness of the Neogene-Quaternary sedimentary cover in the Commander Basin reaches 2 km. In the north, the Bowers Ridge (a former Late Cretaceous volcanic arc) extends in an arc to the north from the Aleutian Islands, outlining the basin of the same name. The maximum depths of the Bering Sea are located in the Kamchatka Strait and near the Aleutian Islands.

Relief and geological structure bottom . According to the nature of the bottom topography, the Bering Sea is clearly divided into shallow and deep-water parts approximately along the line from Cape Navarin to Unimak Island. The northern and southeastern parts lie on a shelf with depths of up to 200 m (prevailing depths are 50-80 m) and a width in the northeast of up to 750 km (46% of the sea area) - one of the widest in the World Ocean. It is a vast plain, slightly inclined to the southwest. In the Quaternary period, the shelf periodically drained and a land bridge emerged between the continents of Eurasia and North America. Within the shelf there are large depressions - Anadyr, Navarin, Khatyr and others, filled with Cenozoic terrigenous deposits. Depressions can be reservoirs of oil and natural combustible gas. A narrow continental slope with depths of 200-3000 m (13%) and with large bottom slopes almost throughout its entire length turns into a deep-sea bed with steep ledges, in many places cut by underwater valleys and canyons. The sides of the canyons are often steep and sometimes steep. In the central and southwestern parts there is a deep-water zone with depths of over 3000 m (37%), bordered in the coastal zone by a narrow strip of shelf. The underwater Shirshov Ridge with depths above the ridge of 500-600 m, stretching south from the Olyutorsky Peninsula, divides the deep-water part of the sea into the Komandorskaya and Aleutian basins; it is separated from the island arc by the Ratmanov Trench (depth about 3500 m). The flat bottom of both basins is slightly inclined to the southwest. The Shirshov Ridge is a complex zone of junction of two lithospheric plates (Commander and Aleutian), along which until the mid-Miocene the oceanic crust piled up (possibly with underthrusting). The foundation of the Aleutian Basin is of Early Cretaceous age and is a fragment of the Mesozoic oceanic lithospheric plate Kula, which separated in the Cretaceous from the Pacific plate by a large transform fault, transformed in the Paleogene into the Aleutian island arc and the deep-sea trench of the same name. The thickness of the Cretaceous-Quaternary sedimentary cover in the central part of the Aleutian Basin reaches 3.5-5 km, increasing towards the periphery to 7-9 km. The foundation of the Commander Basin is Cenozoic in age and was formed as a result of local spreading (the spreading of the bottom with the new formation of oceanic crust), which continued until the end of the Miocene. The paleospreading zone can be traced to the east of Karaginsky Island in the form of a narrow trough. The thickness of the Neogene-Quaternary sedimentary cover in the Commander Basin reaches 2 km. In the north, the Bowers Ridge (a former Late Cretaceous volcanic arc) extends in an arc to the north from the Aleutian Islands, outlining the basin of the same name. The maximum depths of the Bering Sea are located in the Kamchatka Strait and near the Aleutian Islands.

On the shelf, bottom sediments are mainly terrigenous, near the shore - coarse sediments, then sands, sandy silts and silts. The sediments of the continental slope are also predominantly terrigenous, in the area of Bristol Bay - with an admixture of volcanogenic material, and there are numerous outcrops of bedrock. The thickness of sediments in deep-sea basins reaches 2500 m, the surface layer is represented by diatomaceous silt.

Climate. Most of the Bering Sea is characterized by a subarctic climate, in a small area north of 64° north latitude it is arctic, and south of 55° north latitude it is temperate maritime. Climate formation occurs under the influence of the cold masses of the Arctic Ocean in the north, the open spaces of the Pacific Ocean in the south, adjacent land and centers of atmospheric action. In the open part of the Bering Sea, far from the influence of continents, the climate is maritime, mild, with small amplitudes of air temperature fluctuations, the weather is cloudy, with fog and large amounts of precipitation. In winter, under the influence of the Aleutian Low, northwest, north and northeast winds predominate, bringing cold maritime Arctic air, as well as cold, dry continental air. Wind speed off the coast is 6-8 m/s, in the open sea - up to 12 m/s. Often, especially in the western part of the sea, stormy conditions develop with winds up to 30-40 m/s (lasting up to 9 days). The average air temperature in January - February is from 0. -4 °C in the south and southwest to -15. -23 °C in the north and northeast. Off the coast of Alaska, air temperatures dropped to -48 °C. In summer, the influence of the Hawaiian anticyclone increases; southerly winds with speeds of 4-7 m/s prevail over the Bering Sea. In the southern part, on average, tropical typhoons with hurricane-force winds penetrate once a month. The frequency of storms is lower than in winter. The air temperature in the open sea ranges from 4 °C in the north to 13 °C in the south; in coastal areas it is noticeably warmer. Annual precipitation ranges from 450 mm in the northeast to 1000 mm in the southwest.

Climate. Most of the Bering Sea is characterized by a subarctic climate, in a small area north of 64° north latitude it is arctic, and south of 55° north latitude it is temperate maritime. Climate formation occurs under the influence of the cold masses of the Arctic Ocean in the north, the open spaces of the Pacific Ocean in the south, adjacent land and centers of atmospheric action. In the open part of the Bering Sea, far from the influence of continents, the climate is maritime, mild, with small amplitudes of air temperature fluctuations, the weather is cloudy, with fog and large amounts of precipitation. In winter, under the influence of the Aleutian Low, northwest, north and northeast winds predominate, bringing cold maritime Arctic air, as well as cold, dry continental air. Wind speed off the coast is 6-8 m/s, in the open sea - up to 12 m/s. Often, especially in the western part of the sea, stormy conditions develop with winds up to 30-40 m/s (lasting up to 9 days). The average air temperature in January - February is from 0. -4 °C in the south and southwest to -15. -23 °C in the north and northeast. Off the coast of Alaska, air temperatures dropped to -48 °C. In summer, the influence of the Hawaiian anticyclone increases; southerly winds with speeds of 4-7 m/s prevail over the Bering Sea. In the southern part, on average, tropical typhoons with hurricane-force winds penetrate once a month. The frequency of storms is lower than in winter. The air temperature in the open sea ranges from 4 °C in the north to 13 °C in the south; in coastal areas it is noticeably warmer. Annual precipitation ranges from 450 mm in the northeast to 1000 mm in the southwest.

Hydrological regime. The river flow is about 400 km 3 per year. Up to 70% of the flow comes from the Yukon (176 km 3), Anadyr (50 km 3), and Kuskokwim (41 km 3) rivers, with more than 85% of the flow occurring in spring and summer. Compared to the volume of the sea, the amount of fresh flow is small, but river waters flow mainly into the northern regions of the sea, leading to a noticeable desalination of the surface layer in summer. The peculiarities of the hydrological regime are determined by limited water exchange with the Arctic Ocean, relatively free connection with the Pacific Ocean, continental runoff and desalination of water when ice melts. Exchange with the Chukchi Sea is difficult due to the small cross-sectional area of the Bering Strait (3.4 km 2, average depth above the threshold 39 m). The numerous straits connecting the Bering Sea to the Pacific Ocean have a cross-section total area 730 km 2 and depths of over 4000 m (Kamchatka Strait), which contributes to good water exchange with Pacific waters.

In the structure of the Bering Sea, four water masses are mainly distinguished in the deep-sea part: surface, subsurface intermediate cold, intermediate Pacific warm and deep. Salinity changes with depth are small. Both intermediate water masses are absent only near the Aleutian Islands. In certain parts of the Bering Sea, in particular in coastal areas, other water masses are formed depending on local conditions.

Bering Sea surface currents form a counterclockwise gyre, which is significantly influenced by prevailing winds. Along the coast of Alaska to the north follows the Bering Sea branch of the warm Kuroshio currents, which partially leaves through the Bering Strait and, receiving the cold waters of the Chukchi Sea, moves along the Asian coast to the south and forms the cold Kamchatka Current, which intensifies in the summer. The speed of constant currents in the open sea is low, about 6 cm/s; in the straits the speed increases to 25-50 cm/s. In coastal areas, circulation is complicated by periodic tidal currents, reaching 100-200 cm/s in the straits. Tides in the Bering Sea are irregular semidiurnal, irregular diurnal and regular diurnal, their character and magnitude vary greatly from place to place. The average tide height is 1.5-2.0 m, the highest - 3.7 m - is observed in Bristol Bay.

The surface water temperature in February varies from -1.5 °C in the north to 3 °C in the south, in August, respectively, from 4-8 °C to 9-11 °C. The salinity of surface waters in winter is from 32.0‰ in the north to 33.5‰ in the south; in summer, under the influence of melting ice and river runoff, salinity decreases, especially in coastal areas, where it reaches 28‰, in the open part of the sea, respectively, from 31.0‰ in the north to 33‰ in the south. The northern and northeastern parts of the sea are covered with ice every year. The first ice appears in September in the Bering Strait, in the northwest - in October and gradually spreads to the south. During the winter, the Bering Sea is covered with heavy ice up to 60° north latitude. All ice forms and melts in the Bering Sea. Only a small part sea ice carried through the Bering Strait into the Chukchi Sea and by the Kamchatka Current into the northwestern region of the Pacific Ocean. The ice cover collapses and melts in May - June.

History of the study. The Bering Sea is named after the captain-commander of the Russian fleet V. Bering, whose name is associated with the discoveries of the Bering Strait, Aleutian and Commander Islands in the 1st half of the 18th century. Modern name introduced into use in the 1820s by V. M. Golovnin. Previously called Anadyrsky, Bobrovy, Kamchatsky. The first geographical discoveries of the coasts, islands, peninsulas and straits of the Bering Sea were made Russian explorers, fur traders and sailors at the end of the 17th and 18th centuries. Comprehensive studies of the Bering Sea were carried out especially intensively by Russian naval sailors, hydrographers and naturalists until the 1870s. Before the sale of Russian America (1867), the entire coast of the Bering Sea was part of the possession of the Russian Empire.

Economic use. There are about 240 species of fish in the Bering Sea, of which at least 35 are commercial species. Fishing is carried out for cod, flounder, halibut, Pacific perch, herring, and salmon. Kamchatka crab and shrimp are caught. Walruses, sea lions, and sea otters live here. On the Commander and Aleutian Islands there are fur seal rookeries. The open sea is home to baleen whales, sperm whales, beluga whales and killer whales. On the rocky shores there are bird colonies. The Bering Sea is of great transport importance as part of the Northern Sea Route. Main ports- Anadyr, Provideniya (Russia), Nome (USA).

The ecological state of the Bering Sea is consistently satisfactory. The concentration of pollutants increases in river mouths, bays, and ports, which leads to a slight reduction in the size of aquatic organisms in coastal areas.

Lit.: Dobrovolsky A.D., Zalogin B.S. Seas of the USSR. M., 1982; Bogdanov N.A. Tectonics of deep-sea basins of marginal seas. M., 1988; Zalogin B.S., Kosarev A.N. Seas. M., 1999; Dynamics of ecosystems of the Bering and Chukchi Seas. M., 2000.

The Bering Sea is a sea that washes the shores of the United States and Russia, located in the north of the largest ocean in the world - the Pacific.

The Bering Strait connects the Bering Sea with the Arctic Ocean, as well as the Chukchi Sea.

Historical events

The Bering Sea was first mapped only in the 18th century, when it was called the Beaver Sea or Kamchatka Sea.

In 1725, the navigator and officer of the Russian fleet Victor Bering, who had Danish roots, equipped his expedition to explore the then Beaver Sea. Bering passed the strait, which was named after him, and explored the sea, but did not find the coast of North America.

Bering was convinced that the shores of North America were not too far from the shores of Kamchatka, which, if the theory was confirmed, would give the opportunity to trade with American tribes. In 1741, he finally reached the shores of North America, thereby crossing the Kamchatka Sea.

Later, the sea changed its name in honor of the great navigator and geographer - it began to be called the Bering Strait, also as the strait that separates the continents of Eurasia and North America. The sea received its current name only in 1818 - this idea was proposed by French researchers who appreciated Bering's discoveries. However, on maps dating back to the thirties of the 19th century, it was still called Bobrovoye.

Characteristic

The total area of the Bering Sea reaches 2,315,000 square kilometers, and its volume is 3,800,000 cubic kilometers. The deepest point of the Bering Sea is at a depth of 4150 meters, and the average depth does not exceed 1600 meters. Seas like the Bering Sea are usually called marginal, because it is located on the very edge of the Pacific Ocean. It is this sea that separates two large continents: North America and Asia.

Quite impressive coastline It consists mainly of capes and small bays - the coast is simply indented by them. Only a couple flow into the Bering Sea big rivers: the North American Yukon River, whose length reaches more than three thousand kilometers, and the Russian Anadyr River, which is much shorter - only 1150 km.

The climate is influenced by arctic air masses that collide with southern warm ones coming from tropical and temperate latitudes. As a result, a cold climate is formed - the weather is unstable, there are prolonged (about a week) storms. The wave height reaches 7 - 12 meters.

Since the Bering Sea is located in the northern latitudes, from the beginning of September the temperature here drops to minus and the surface of the water is covered with a layer of ice. The ice in the Bering Sea only melts in July, which means that it is only ice-free for two months. The Bering Strait is not covered with ice due to the current. The salt level in the water fluctuates from 33 to 34.7%.

Bering Sea. sunset photo

Bering Sea. sunset photo

In summer, the water surface temperature reaches approximately 7-10 degrees Celsius. However, in winter the temperature drops seriously and reaches -3 degrees Celsius. The intermediate layer of water is constantly cold - its temperature never rises above -1.7 degrees - this applies to the layer from 50 to 200 meters. And water at a depth of 1000 meters reaches approximately -3 degrees.

Relief

The bottom topography is very heterogeneous, often transitioning into deep depressions. In the south is the deepest point of the sea at more than four thousand meters. There are also several underwater ridges at the bottom. The seabed is mainly covered with shell rock, sand, diatomaceous earth and gravel.

Cities

There are few cities on the shores of the Bering Sea, and certainly none of them are large due to the very remote location from civilization and the harsh weather throughout the year. However, attention should be paid to the following cities:

- Provideniya is a small port settlement that was founded in the middle of the 17th century as a bay for fishing - mainly whaling ships stood here. Only in the middle of the 20th century did construction of a port begin here, which led to the construction of a town around it. The official founding date of Providence is 1946. Now the population of the town is only slightly more than 2 thousand people;

- Nome is an American town in the state of Alaska, where, according to the latest census, almost four thousand people live. Nome was founded as a settlement of gold miners in 1898, and the next year its population was about 10 thousand - everyone fell ill with the “gold rush”. Already in the thirties of the 20th century, the boom of the “gold rush” came to naught and a little more than a thousand inhabitants remained in the city;

Anadyr photo

Anadyr photo

- Anadyr is one of the largest cities on the coast, whose population exceeds 14 thousand inhabitants and is constantly growing. The city is located in a zone of almost permafrost. There is a large port of the same name and a fish factory here. In addition, gold and coal are mined in the vicinity of the city. The population also breeds deer, engages in fishing and, of course, hunting.

Animal world

Despite the fact that the Bering Sea is quite cold, this does not prevent it from being home to many species of fish, the number of which reaches more than four hundred and all of them are widespread, with a few exceptions. These four hundred hundred species of fish include seven species of salmon, about nine species of gobies, five species of eelpout, and four species of flounder.

Birds over the Bering Sea photo

Birds over the Bering Sea photo

Of the four hundred species, 50 of them are industrial fish. Also objects for industrial production are four species of crabs, two species of cephalopods and four species of shrimp.

Among the mammals, one can note a large population of seals, including ringed seals, bearded seals, harbor seals, Pacific walruses and lionfish. Walruses and seals form huge rookeries on the coast of Chukotka.

Bereng Sea. Walruses photo

Bereng Sea. Walruses photo

In addition to pinnipeds, cetaceans are also found in the Bering Sea, including quite rare species such as narwhals, humpback whales, bowhead whales, southern or Japanese whales, incredibly rare northern blue whales and no less rare fin whales.

- The Gulf of Lawrence, which in the Bering Sea sometimes does not clear ice on its surface for years at all;

- The city of Nome on the Bering Sea coast hosts the most prestigious husky races and is also where the true story, which formed the basis for the cartoon Balto, where a dog saved children from diphtheria.

Bering Sea

The largest of the Far Eastern seas washing the shores of Russia, the Bering Sea is located between two continents - Asia and North America - and is separated from the Pacific Ocean by the islands of the Commander-Aleutian Arc. Its northern border coincides with the southern border of the Bering Strait and stretches along the line of Cape Novosilsky (Chukchi Peninsula) - Cape York (Seward Peninsula), the eastern border runs along the coast of the American continent, the southern - from Cape Khabuch (Peninsula Alaska) through the Aleutian Islands to Cape Kamchatsky, western - along the coast of the Asian continent.

The Bering Sea is one of the largest and deepest seas in the world. Its area is 2315 thousand km 2, volume - 3796 thousand km 3, average depth - 1640 m, greatest depth - 4097 m. The area with depths less than 500 m occupies about half of the entire area of the Bering Sea, which belongs to the marginal seas of mixed continental -oceanic type.

There are few islands in the vast expanses of the Bering Sea. Not counting the border Aleutian island arc and the Commander Islands, the sea contains the large Karaginsky Islands in the west and several islands (St. Lawrence, St. Matthew, Nelson, Nunivak, St. Paul, St. George, Pribilof) in the east.

The coastline of the Bering Sea is highly indented. It forms many bays, bays, peninsulas, capes and straits. For the formation of many natural processes of this sea, straits that ensure water exchange with the Pacific Ocean are especially important. Their total cross-sectional area is approximately 730 km 2, the depths in some of them reach 1000-2000 m, and in Kamchatka - 4000-4500 m, as a result of which water exchange occurs not only in the surface, but also in the deep horizons. The cross-sectional area of the Bering Strait is 3.4 km 2, and the depth is only 60 m. The waters of the Chukchi Sea have practically no effect on the Bering Sea, but the Bering Sea waters play a very significant role in the Chukchi Sea.

Boundaries of the Pacific Ocean

Different areas of the Bering Sea coast belong to different geomorphological types of shores. Mostly the shores are abrasive, but there are also accumulative ones. The sea is surrounded mainly by high and steep shores; only in the middle part of the western and eastern coasts are wide strips of flat, low-lying tundra approaching it. Narrower strips of low-lying coastline are located near the mouths of small rivers in the form of a deltaic alluvial valley or border the tops of bays and bays.

Landscapes of the Bering Sea coast

Bottom relief

In the bottom topography of the Bering Sea, the main morphological zones are clearly distinguished: the shelf and island shoals, the continental slope and the deep-sea basin. The shelf zone with depths of up to 200 m is mainly located in the northern and eastern parts of the sea and occupies more than 40% of its area. Here it adjoins the geologically ancient regions of Chukotka and Alaska. The bottom in this area is a vast, very flat underwater plain 600-1000 km wide, within which there are several islands, troughs and small rises in the bottom. The mainland shelf off the coast of Kamchatka and the islands of the Komandorsko-Aleutian ridge looks different. Here it is narrow, and its relief is very complex. It borders the shores of geologically young and very mobile land areas, within which intense and frequent manifestations of volcanism and seismic activity are common.

The continental slope stretches from northwest to southeast approximately along the line from Cape Navarin to the island. Unimak. Together with the island slope zone, it occupies approximately 13% of the sea area, has depths from 200 to 300 m and is characterized by complex bottom topography. The continental slope zone is dissected by underwater valleys, many of which are typical underwater canyons, deeply cut into the seabed and having steep and even steep slopes. Some canyons, especially near the Pribilof Islands, have a complex structure.

The deep-water zone (3000-4000 m) is located in the southwestern and central parts of the sea and is bordered by a relatively narrow strip of coastal shallows. Its area exceeds 40% of the sea area. The bottom topography is very calm. It is characterized by an almost complete absence of isolated depressions. The slopes of some bottom depressions are very gentle, i.e. these depressions are weakly isolated. Among the positive forms, the Shirshov Ridge stands out, but it has a relatively small depth on the ridge (mostly 500–600 m with a saddle of 2500 m) and does not approach the base of the island arc closely, but ends in front of the narrow but deep (about 3500 m) Ratmanov Trench. The greatest depths of the Bering Sea (more than 4000 m) are located in the Kamchatka Strait and near the Aleutian Islands, but they occupy a small area. Thus, the bottom topography makes it possible for water exchange between individual parts of the sea: without restrictions within the depths of 2000-2500 m and with some limitation (determined by the cross-section of the Ratmanov Trench) to depths of 3500 m.

Bottom topography and currents of the Bering Sea

Climate

Geographical location and large spaces determine the main features of the climate of the Bering Sea. It is almost entirely located in the subarctic climate zone, only the northernmost part (north of 64° N) belongs to the Arctic zone, and the southernmost part (south of 55° N) belongs to the temperate latitude zone. In accordance with this, climatic differences between different areas of the sea are determined. North of 55-56° N In the climate of the sea (especially its coastal areas), continental features are noticeably expressed, but in areas remote from the coast they are much less pronounced. To the south of these parallels the climate is mild, typically maritime. It is characterized by small daily and annual air temperature amplitudes, large clouds and significant amounts of precipitation. As you approach the coast, the influence of the ocean on the climate decreases. Due to stronger cooling and less significant heating of the part of the Asian continent adjacent to the sea, the western regions of the sea are colder than the eastern ones. Throughout the year, the Bering Sea is under the influence of constant centers of atmospheric action - the Polar and Hawaiian maxima, the position and intensity of which vary from season to season, and the degree of their influence on the sea changes accordingly. It is no less influenced by seasonal large-scale pressure formations: the Aleutian minimum, the Siberian maximum, and the Asian depression. Their complex interaction determines the seasonal characteristics of atmospheric processes.

In the cold season, especially in winter, the sea is influenced mainly by the Aleutian minimum, the Polar maximum and the Yakut spur of the Siberian anticyclone. Sometimes the impact of the Hawaiian High, which at this time occupies the extreme southern position, is felt. Such a synoptic situation leads to a wide variety of winds and the entire meteorological situation over the sea. At this time, winds from almost all directions are observed here. However, the northwestern, northern and northeastern ones noticeably predominate. Their total repeatability is 50-70%. Only in the eastern part of the sea, south of 50° N, are southern and southwestern winds quite often observed, and in some places even southeastern. Wind speed in the coastal zone averages 6-8 m/s, and in open areas it varies from 6 to 12 m/s, increasing from north to south. Winds from the northern, western and eastern directions carry with them cold sea arctic air from the Arctic Ocean, and cold and dry continental polar and continental arctic air from the Asian and American continents. With winds from the south, polar sea air and, at times, tropical sea air comes here. Above the sea, predominantly the masses of continental Arctic and marine polar air interact, at the border of which an Arctic front is formed. It is located slightly north of the Aleutian arc and generally stretches from southwest to northeast. At the frontal section of these air masses, cyclones form, moving approximately along the front to the northeast. The movement of these cyclones increases northern winds in the west and weakening them or even changing them to the south in the east of the sea. Large pressure gradients caused by the Yakut spur of the Siberian anticyclone and the Aleutian low cause very strong winds in the western part of the sea. During storms, wind speeds often reach 30-40 m/s. Usually storms last about a day, but sometimes they last 7-9 days with some weakening. The number of days with storms in the cold season is 5-10, in some places it reaches 15-20 per month.

Water temperature on the surface of the Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk in summer

Air temperature in winter decreases from south to north. The average monthly temperature of the coldest months - January and February - is 1-4° in the southwestern and southern parts of the sea and -15-20° in the northern and northeastern regions. In the open sea the air temperature is higher than in the coastal zone. Off the coast of Alaska it can drop to –40-48°. In open spaces, temperatures below –24° are not observed.

In the warm season, a restructuring of pressure systems occurs. Starting in spring, the intensity of the Aleutian minimum decreases, and in summer it is very weakly expressed, the Yakut spur of the Siberian anticyclone disappears, the Polar Maximum shifts to the north, and the Hawaiian Maximum takes its extreme northern position. As a result of this synoptic situation, in warm seasons southwestern, southern and southeastern winds predominate, the frequency of which is 30-60%. Their speed in the western part of the open sea is 4-6 m/s, and in the eastern regions - 4-7 m/s. In the coastal zone, wind speed is lower. The decrease in wind speeds compared to winter values is explained by a decrease in atmospheric pressure gradients over the sea. In summer, the Arctic front moves south of the Aleutian Islands. Cyclones originate here, the passage of which is associated with a significant increase in winds. In summer, the frequency of storms and wind speeds are lower than in winter. Only in the southern part of the sea, where tropical cyclones (typhoons) penetrate, do they cause severe storms with hurricane-force winds. Typhoons in the Bering Sea are most likely from June to October, usually occurring no more than once a month and lasting several days. Air temperature in summer generally decreases from south to north, and it is slightly higher in the eastern part of the sea than in the western. Average monthly air temperatures in the warmest months - July and August - within the sea vary from approximately 4° in the north to 13° in the south, and they are higher near the coast than in the open sea. Relatively mild winters in the south and cold winters in the north, and cool, cloudy summers everywhere are the main seasonal weather features in the Bering Sea. Continental flow into the sea is approximately 400 km 3 per year. Most of the river water falls into its northernmost part, where the largest rivers flow: Yukon (176 km 3), Kuskokwim (50 km 3 / year) and Anadyr (41 km 3 / year). About 85% of the total annual flow occurs in the summer months. The influence of river waters on sea waters is felt mainly in the coastal zone on the northern edge of the sea in the summer.

Hydrology and water circulation

Geographical location, vast spaces, relatively good communication with the Pacific Ocean through the straits of the Aleutian ridge in the south and extremely limited communication with the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Strait in the north determine the hydrological conditions of the Bering Sea. The components of its heat budget depend mainly on climatic conditions and, to a much lesser extent, on heat advection by currents. In this regard, various climatic conditions in the northern and southern parts of the sea entail differences in the thermal balance of each of them, which accordingly affects the water temperature in the sea.

On the contrary, water exchange is of decisive importance for the water balance of the Bering Sea. Very large quantities of surface and deep ocean water flow through the Aleutian Straits, and water flows through the Bering Strait into the Chukchi Sea. Precipitation (about 0.1% of the volume of the sea) and river flow (about 0.02%) are very small in relation to the huge area and volume of sea waters, and therefore are less significant in the water balance than water exchange through the Aleutian Straits.

However, water exchange through these straits has not yet been sufficiently studied. It is known that large masses of surface water exit the sea into the ocean through the Kamchatka Strait. The overwhelming mass of deep ocean water enters the sea in three areas: through the eastern half of the Near Strait, through almost all the straits of the Fox Islands and through the Amchitka, Tanaga and other straits between the Rat and Andrianovsky Islands. It is possible that deeper waters penetrate into the sea through the Kamchatka Strait, if not constantly, then periodically or sporadically. Water exchange between the sea and the ocean affects the distribution of temperature, salinity, formation of the structure and general circulation of the waters of the Bering Sea.

The bulk of the waters of the Bering Sea are characterized by a subarctic structure, the main feature of which is the existence of a cold intermediate layer in summer, as well as a warm intermediate layer located below it. Only in the southernmost part of the sea, in areas immediately adjacent to the Aleutian ridge, waters of a different structure were discovered, where both intermediate layers are absent.

Water temperature and salinity

Salinity on the surface of the Bering and Okhotsk seas in summer

The bulk of the waters of the sea, which occupies its deep-sea part, is clearly divided into four layers in summer: surface, cold intermediate, warm intermediate and deep. This stratification is determined mainly by differences in temperature, and the change in salinity with depth is small.

The surface water mass in summer is the most heated upper layer from the surface to a depth of 25-50 m, characterized by a temperature of 7-10° at the surface and 4-6° at the lower boundary and a salinity of about 33‰. The greatest thickness of this water mass is observed in the open part of the sea. The lower boundary of the surface water mass is the temperature jump layer. The cold intermediate layer is formed here as a result of winter convective mixing and subsequent summer heating of the upper layer of water. This layer has insignificant thickness in the southeastern part of the sea, but as it approaches the western shores it reaches 200 m or more. The minimum temperature was noted at horizons of about 150-170 m. In the eastern part, the minimum temperature is 2.5-3.5 °, and in the western part of the sea it drops to 2 ° in the area of the Koryak coast and to 1 ° and lower in the area of Karaginsky Bay. The salinity of the cold intermediate layer is 33.2-33.5‰ At the lower boundary of this layer, the salinity quickly increases to 34‰.

Vertical distribution of water temperature (1) and salinity (2) in the Bering Sea

IN warm years in the south, in the deep-water part of the sea, the cold intermediate layer may be absent in summer, then the temperature decreases relatively smoothly with depth with a general warming of the entire water column. The origin of the intermediate layer is associated with the influx of Pacific water, which is cooled from above as a result of winter convection. Convection reaches horizons of 150-250 m here, and under its lower boundary an increased temperature is observed - a warm intermediate layer. The maximum temperature varies from 3.4-3.5 to 3.7-3.9°. The depth of the core of the warm intermediate layer in the central regions of the sea is approximately 300 m, to the south it decreases to 200 m, and to the north and west it increases to 400 m or more. The lower boundary of the warm intermediate layer is blurred, approximately it is outlined in the layer of 650-900 m.

The deep water mass, which occupies most of the volume of the sea, does not differ significantly both in depth and in sea area. Over a distance of more than 3000 m, the temperature varies from approximately 2.7-3.0 to 1.5-1.8 ° at the bottom. Salinity is 34.3-34.8‰.

As we move south to the straits of the Aleutian ridge, the stratification of waters is gradually erased, the temperature of the core of the cold intermediate layer increases, approaching in value the temperature of the warm intermediate layer. The waters gradually acquire a qualitatively different structure than Pacific water.

In some areas, especially in shallow waters, the main water masses change, new masses appear that have local significance. For example, in the western part of the Gulf of Anadyr, a desalinated water mass is formed under the influence of continental runoff, and in the northern and eastern parts, a cold water mass of the Arctic type is formed. There is no warm intermediate layer here. In some shallow areas of the sea, cold waters are observed in the bottom layer in summer. Their formation is associated with the vortex water cycle. The temperature in these cold “spots” drops to –0.5-1°.

Due to autumn-winter cooling, summer heating and mixing in the Bering Sea, the surface water mass is most strongly transformed, as well as the cold intermediate layer. Intermediate Pacific water changes its characteristics very slightly throughout the year and only in a thin upper layer. Deep waters do not change noticeably throughout the year.

The water temperature on the sea surface generally decreases from south to north, with water in the western part of the sea being somewhat colder than in the eastern part. In winter, in the south-western part of the sea the surface water temperature is usually 1-3°, and in the eastern part - 2-3°. In the north throughout the sea, water temperatures range from 0° to –1.5°. In spring, the water begins to warm up and the ice begins to melt, while the temperature rises slightly. In summer, the surface water temperature is 9-11° in the south of the western part and 8-10° in the south of the eastern part. In the northern regions of the sea it is 4° in the west and 4-6° in the east. In coastal shallow areas, surface water temperatures are slightly higher than in open areas of the Bering Sea.

The vertical distribution of water temperature in the open part of the sea is characterized by seasonal changes up to horizons of 150-200 m, deeper than which they are practically absent.

Scheme of water exchange in the Okhotsk and Bering Seas

In winter, the surface temperature, equal to approximately 2°, extends to horizons of 140-150 m, below it rises to approximately 3.5° at horizons of 200-250 m, then its value almost does not change with depth.

In spring, the water temperature on the surface rises to approximately 3.8° and remains up to horizons of 40-50 m, then to horizons of 65-80 m it sharply, and then (up to 150 m) very smoothly decreases with depth and from a depth of 200 m it increases slightly to the bottom.

In summer, the water temperature on the surface reaches 7-8°, but drops very sharply (up to 2.5°) with a depth to the horizon of 50 m; below its vertical course is almost the same as in spring.

In general, the water temperature in the open part of the Bering Sea is characterized by a relative homogeneity of spatial distribution in the surface and deep layers and relatively small seasonal fluctuations, which appear only to horizons of 200-300 m.

The salinity of surface waters of the sea varies from 33-33.5‰ in the south to 31‰ in the east and northeast and up to 28.6‰ in the Bering Strait. Water is most significantly desalinated in spring and summer in the areas where the Anadyr, Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers confluence. However, the direction of the main currents along the coasts limits the influence of continental runoff on the deep sea areas.

The vertical distribution of salinity is almost the same in all seasons of the year. From the surface to the horizon of 100-125 m, it is approximately equal to 33.2-33.3‰. Salinity increases slightly from horizons of 125-150 to 200-250 m; deeper it remains almost unchanged to the bottom.

In accordance with small spatiotemporal changes in temperature and salinity, density also changes slightly. The distribution of oceanological characteristics by depth indicates a relatively weak vertical stratification of the waters of the Bering Sea. In combination with strong winds, this creates favorable conditions for the development of wind mixing. In the cold season, it covers the upper layers up to horizons of 100-125 m; in the warm season, when the waters are stratified more sharply and the winds are weaker than in autumn and winter, wind mixing penetrates to horizons of 75-100 m in the deep and up to 50-60 m in coastal areas.

Significant cooling of waters, and in the northern regions, intensive ice formation, contribute to the good development of autumn-winter convection in the sea. During October - November it captures the surface layer of 35-50 m and continues to penetrate deeper.

The penetration boundary of winter convection deepens as it approaches the coast due to enhanced cooling near the continental slope and shallows. In the southwestern part of the sea this decrease is especially large. This is associated with the observed lowering of cold waters along the coastal slope.

Due to the low air temperature due to the high latitude of the northwestern region, winter convection develops here very intensively and, probably, already in mid-January (due to the shallowness of the region) reaches the bottom.

Currents

As a result of the complex interaction of winds, the influx of water through the straits of the Aleutian ridge, tides and other factors, a field of constant currents in the sea is created.

The majority of ocean water enters the Bering Sea through eastern part Blizhny Strait, as well as through other significant straits of the Aleutian ridge.

Waters entering through the Blizhny Strait and spreading first into east direction, then turn north. At a latitude of about 55°, these waters merge with the waters coming from the Amchitka Strait, forming the main flow of the central part of the sea. This flow supports the existence of two stable gyres here - a large, cyclonic one, covering the central deep-water part of the sea, and a smaller, anticyclonic one. The waters of the main flow are directed to the northwest and reach almost the Asian shores. Here, most of the water turns along the coast to the southwest, giving rise to the cold Kamchatka Current, and enters the ocean through the Kamchatka Strait. Some of this water is discharged into the ocean through the western part of the Blizhny Strait, and a very small part is included in the main circulation.

Waters entering through eastern straits The Aleutian ridge also crosses the central basin and moves to the north-northwest. At approximately latitude 60°, these waters divide into two branches: the northwestern one, moving towards the Gulf of Anadyr and then northeast into the Bering Strait, and the northeastern one, moving towards Norton Sound and then north into the Bering Strait. strait

The speeds of constant currents in the sea are low. The highest values (up to 25-50 cm/s) are observed in the areas of the straits, and in the open sea they are equal to 6 cm/s, and the speeds are especially low in the zone of the central cyclonic circulation.

Tides in the Bering Sea are mainly caused by the propagation of tidal waves from the Pacific Ocean.

In the Aleutian Straits, the tides have irregular diurnal and irregular semidiurnal patterns. Off the coast of Kamchatka, during intermediate phases of the Moon, the tide changes from semidiurnal to daily; at high declinations of the Moon it becomes almost purely diurnal, and at low declinations it becomes semidiurnal. On the Koryak coast, from Olyutorsky Bay to the mouth of the river. Anadyr, the tide is irregular semi-diurnal, but off the coast of Chukotka it is regular semi-diurnal. In the area of Provideniya Bay, the tide again becomes irregularly semidiurnal. In the eastern part of the sea, from Cape Prince of Wales to Cape Nome, the tides have both regular and irregular semidiurnal patterns.

South of the mouth of the Yukon, the tide becomes irregularly semidiurnal.

Tidal currents in the open sea are circular in nature, and their speed is 15-60 cm/s. Near the coast and in the straits, tidal currents are reversible, and their speed reaches 1-2 m/s.

Cyclonic activity developing over the Bering Sea causes the occurrence of very strong and sometimes prolonged storms. Particularly strong excitement develops from November to May. At this time of year, the northern part of the sea is covered with ice, and therefore the strongest waves are observed in the southern part. Here in May the frequency of waves of more than 5 points reaches 20-30%, and in the northern part of the sea it is absent due to ice. In August, waves and swells over 5 points reach their greatest development in the eastern part of the sea, where the frequency of such waves reaches 20%. In autumn, in the southeastern part of the sea, the frequency of strong waves is up to 40%.

With prolonged winds of average strength and significant acceleration of waves, their height reaches 6-8 m, with winds of 20-30 m/s or more - up to 10 m, and in some cases - up to 12 and even 14 m. Periods of storm waves reach up to 9-11 s, and with moderate waves - up to 5-7 s.

Kunashir Island

In addition to wind waves, a swell is observed in the Bering Sea, the greatest frequency of which (40%) occurs in autumn. In the coastal zone, the nature and parameters of waves are very different depending on the physical and geographical conditions of the area.

Ice cover

For most of the year, much of the Bering Sea is covered in ice. Ice in the sea is of local origin, i.e. are formed, destroyed and melted into the sea itself. A small amount of ice from the Arctic basin, which usually does not penetrate south of the island, is brought into the northern part of the sea through the Bering Strait by winds and currents. St. Lawrence.

Ice conditions in the northern and southern parts of the sea differ. The approximate boundary between them is the extreme southern position of the ice during the year - in April. This month the edge runs from Bristol Bay through the Pribilof Islands and further west along the 57-58th parallel, and then drops south to the Commander Islands and runs along the coast to the southern tip of Kamchatka. Southern part The sea doesn't freeze at all. Warm Pacific waters entering the Bering Sea through the Aleutian Straits push floating ice to the north, and the edge of the ice in the central part of the sea is always curved to the north.

The process of ice formation begins first in the northwestern part of the Bering Sea, where ice appears in October and gradually moves south. Ice appears in the Bering Strait in September. In winter, the strait is filled with solid broken ice, drifting north.

In the Gulf of Anadyr and Norton Sound, ice can be found as early as September. In early November, ice appears in the area of Cape Navarin, and in mid-November it spreads to Cape Olyutorsky. Off the coast of Kamchatka and the Commander Islands, floating ice usually appears in December and only as an exception in November. During winter, the entire northern part of the sea, up to approximately the 60° parallel, is filled with heavy, hummocky ice, the thickness of which reaches 6-10 m. To the south of the parallel, the Pribilof Islands are found broken ice and isolated ice fields.

However, even during the peak of ice formation, the open part of the Bering Sea is never covered with ice. In the open sea, under the influence of winds and currents, ice is in constant motion, and strong compression often occurs. This leads to the formation of hummocks, the maximum height of which can reach up to 20 m. Due to periodic compression and rarefaction of ice associated with tides, piles of ice, numerous polynyas and clearings are formed.

Fixed ice, which forms in closed bays and bays in winter, can be broken up and carried out to sea during stormy winds. The ice from the eastern part of the sea is carried north into the Chukchi Sea.

In April the border floating ice moves as far as possible to the south. From May, the ice begins to gradually collapse and retreat to the north. During July and August the sea is completely clear of ice, but even during these months ice can be found in the Bering Strait. Strong winds contribute to the destruction of the ice cover and the clearing of ice from the sea in summer.

In bays and bays, where the desalinating influence of river flow is felt, conditions for ice formation are more favorable than in the open sea. Winds have a great influence on the location of ice. Surge winds often clog individual bays, bays and straits heavy ice brought from the open sea. On the contrary, rushing winds carry ice out to sea, sometimes clearing the entire coastal area.

Bird market

Economic importance

Fish of the Bering Sea are represented by more than 400 species, of which only no more than 35 are considered important commercial species. These are salmon, cod, and flounder. Perch, grenadier, capelin, sable fish, etc. are also caught in the sea.